Conservation of Energy & Linear Momentum with Ballistic Pendulum & Projectile Motion#

Background#

OVERALL GOALS

Use a ballistic pendulum to:

Determine initial exit velocities of a projectile to investigate and compare two different techniques:

Motion explained by conservation of linear momentum and mechanical energy

Motion explained by kinematics

DO NOT FIRE LAUNCHER WITHOUT BALL

To prevent damage to the piston, please only fire the spring-loaded piston gun with a ball loaded. Damage has been done before, therefore this note is now here. Thanks.

Two techniques will be employed today.

In the first, a ballistic pendulum, a device designed to capture a projectile in an initially stationary pendulum, will be used. The conservation principles are used to analyze the collision and the subsequent motion of the pendulum. The completely inelastic collision associated with the capture of the projectile in the pendulum and the subsequent motion of the pendulum provide the data necessary for the determination of the initial exit velocity.

In the second technique, the measured parameters of the trajectory of a horizontally launched projectile are used to determine the initial exit velocity. With the projectile moving in a free-fall trajectory, constant acceleration kinematics will be used to determine the initial exit velocity from measurements of the horizontal range and vertical drop.

In each case, the projectile will be launched with the same device allowing a comparison of the initial exit velocity determinations of the two techniques.

Ballistic Pendulum Review#

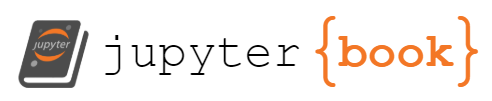

The ballistic pendulum is so named because it was originally used to measure the velocity of high-speed projectiles such as bullets long before electric and electronic timers made the procedure unnecessary. It remains, however, as a simple and demonstrative device for understanding the conservation principles of energy and momentum. In analyzing the problem, the system will consist of the projectile and the more massive pendulum (see Fig. 46).

Fig. 46 Left) Ballistic pendulum apparatus showing path of the rotating arm during the pendulum experiment. Right) Arm with metal bob that catches the projectile (metal ball with hole, not shown) when launched from the spring-powered gun of the apparatus.#

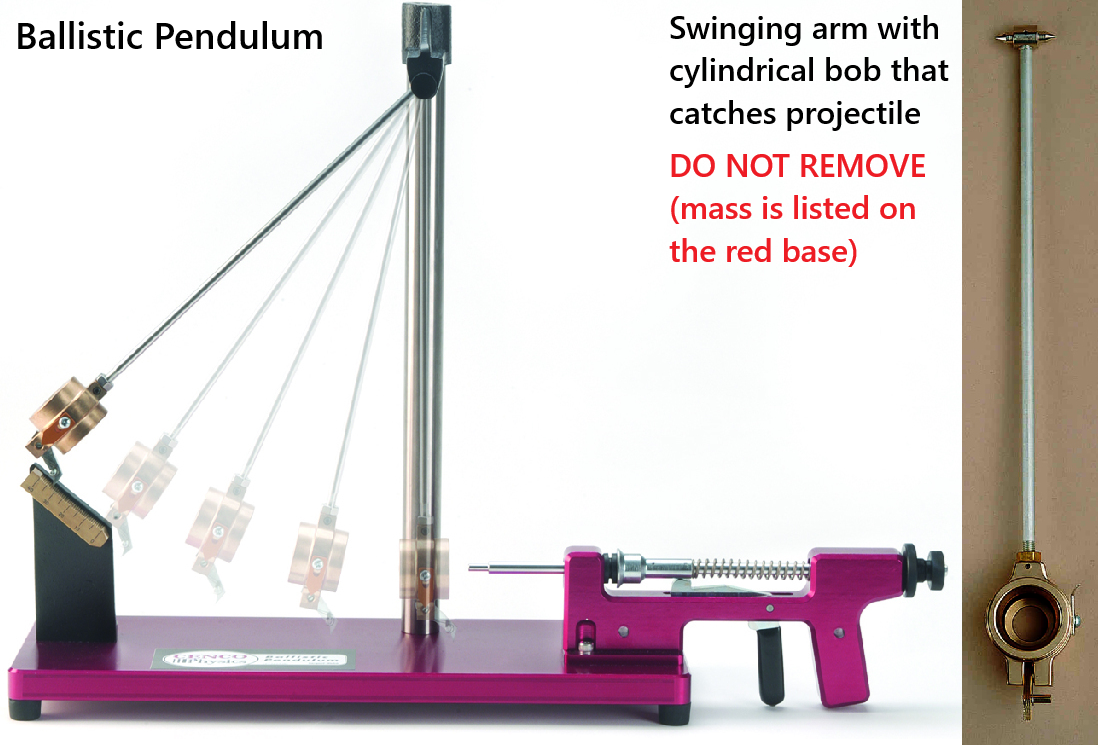

As illustrated in the left image in Fig. 47, before the collision, the projectile is in motion horizontally towards the stationary pendulum. After the collision, the projectile is imbedded in the pendulum and the pendulum is moving along the arc as shown in the right image of Fig. 47.

Fig. 47 Ballistic Pendulum before (left) and after the collision (right)#

The horizontally launched brass ball collides rather violently with and is captured by the more massive bob of the pendulum, initially at rest. The violent collision is totally inelastic as the ball is captured by the pendulum with much of the initial kinetic energy of the ball lost through a variety of energy conversions, mostly heat.

During the collision of the ball with the pendulum, no external forces are acting on the system. Newton’s third law demands that the forces of the ball on the pendulum and the pendulum on the ball are equal and opposite. These two, always equal and opposite, internal forces are acting for the same time and therefore produce equal and opposite impulses on the two bodies. Thus the change in momentum of one body is equal and opposite to the change in momentum of the other. If the momentum changes of the two colliding bodies are equal and opposite, then the total linear momentum of the system cannot change and the total momentum is conserved.

Notice that there has been no assumption on the nature of the internal forces acting. They do not have to be elastic, i.e. conservative. As such, the conservation of momentum does not imply anything about the conservation of kinetic energy in the collision. Linear momentum is conserved regardless of the nature of the interaction of the two bodies during the collision. Only when the interactive forces are completely elastic, i.e. conservative, will the kinetic energy of the collision be conserved.

Momentum, like force and velocity, is a vector quantity. The conservation of momentum of a system therefore implies the conservation of the total vector momentum of the system. In our case, the initial momentum of the system is the initial momentum of the brass ball, which is only in the horizontal direction. Therefore the momentum after the collision can only be in the horizontal direction and they must be equal.

Thus we can write

where \(m\) is the mass of the ball, \(M\) is the mass of the pendulum, and \(\vec{V}\) is the velocity of the pendulum and ball together. If we can measure or determine \(\vec{V}\), we can determine \(\vec{v}_0\). The determination of \(\vec{V}\) can be made by examining the motion of the pendulum after the collision.

After the collision, the pendulum swings upward until it momentarily comes to rest at the top of its swing where the vertical height of the system has been increased from \(y_1\) to \(y_2\) (right image of Fig. 47). We will now make some assumptions. We will assume that there are no friction losses in the motion of the pendulum and that no collisions take place that might otherwise cause a loss of mechanical energy. In other words, we are assuming that the total mechanical energy of the system is conserved after the collision. By equating the kinetic energy of the system just after the collision at the bottom of the swing to the potential energy at the top, we can write

Solving this expression for \(V\) we have

Substituting in (63) above, we have finally an expression for the initial exit velocity of the ball in terms of the measurable change in height of the pendulum and the respective masses, i.e.

Projectile Motion Review#

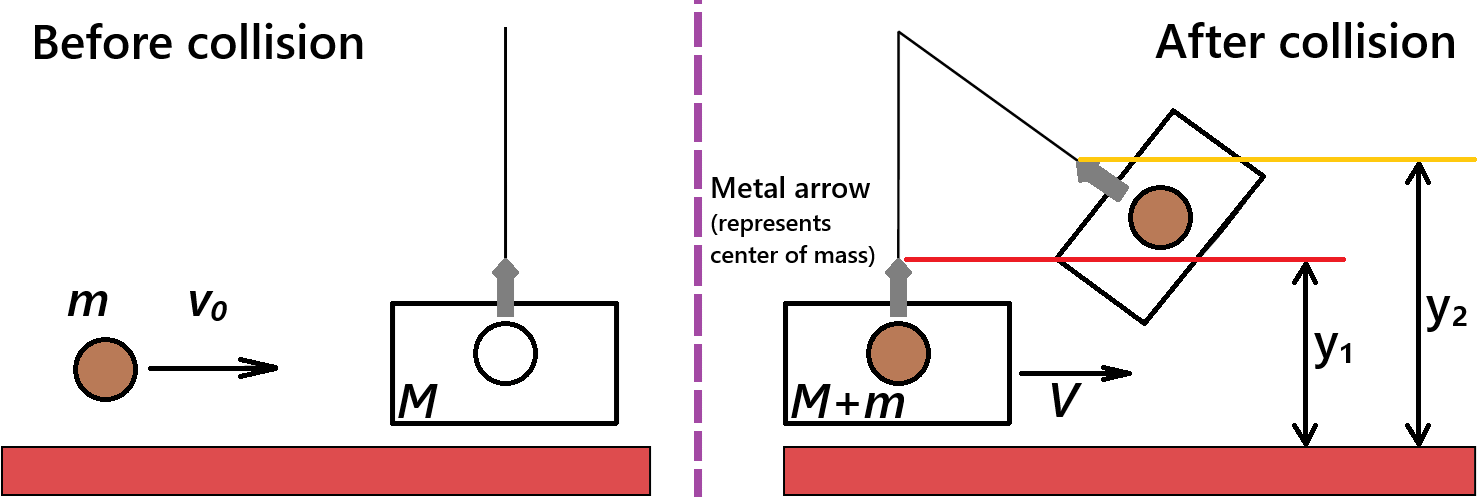

When a projectile is moving solely under the influence of the force of gravity, we say that the projectile is in free-fall. Consider the launching of the same ball used in the ballistic pendulum. In this case, the pendulum will be swung up out of the way so the flight of the ball will continue off the edge of the table, eventually hitting the floor some distance away. This situation is illustrated in Fig. 48.

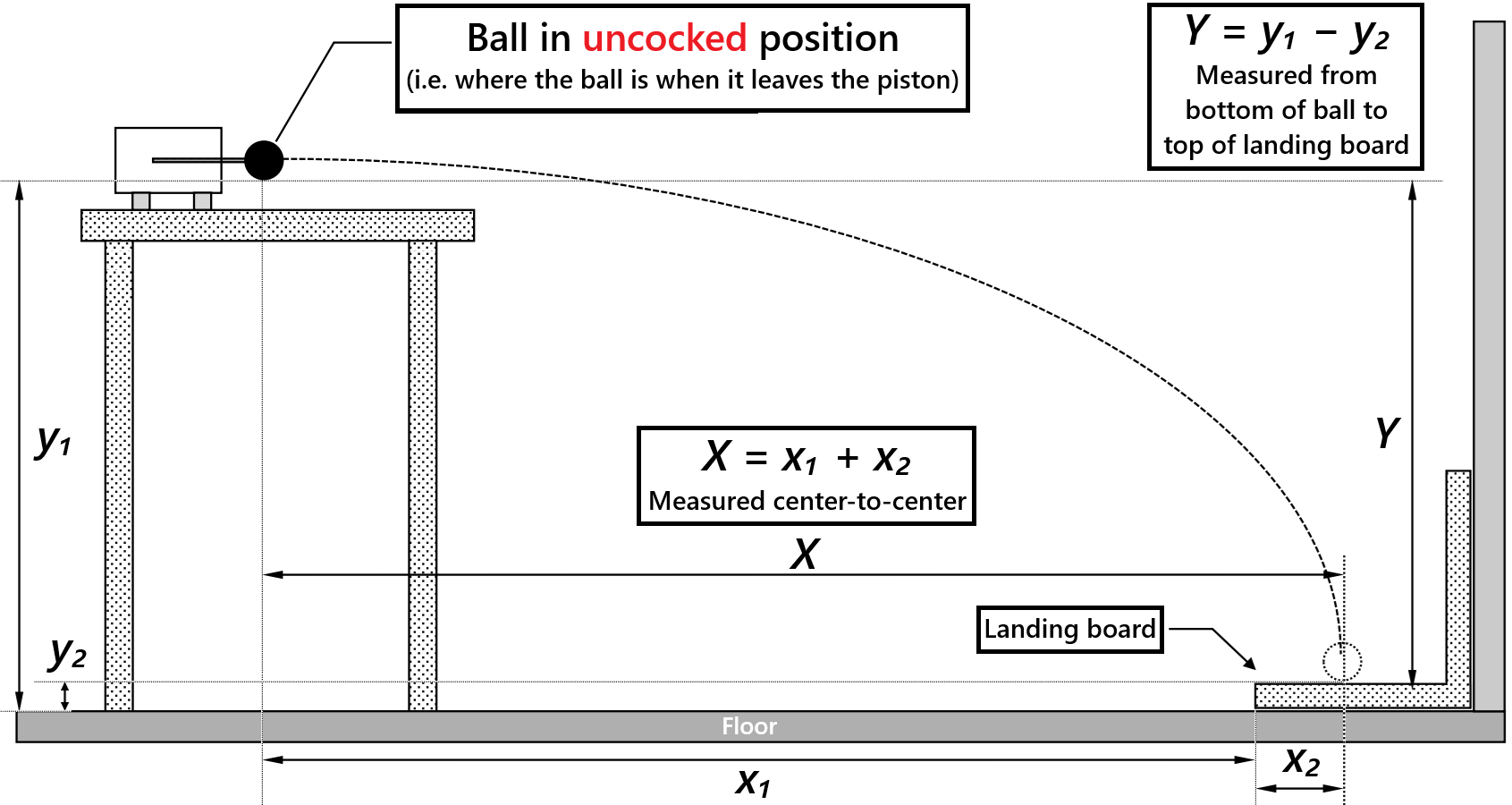

Fig. 48 Projectile Motion. Note \(X\) and \(Y\) are broken down into easier-to-measure quantities.#

Once the ball leaves the spring gun used to launch the ball, the ball is in free-fall. The vertical and horizontal motions are completely independent. We assume that once the ball leaves the gun, there are no energy loss mechanisms during the flight of the ball.

In the vertical direction, the initial velocity is zero and the ball is accelerated downward by its weight, finally hitting the floor some time, \(t\), later, dropping a vertical distance of \(Y\), measured from the bottom of the ball to the top of the landing pad. In the horizontal direction, the ball has a constant velocity of \(v_0\) during the entire flight over the horizontal distance \(X\), measured from the bottom of the ball to the center of the impact mark on the landing pad.

Using our kinematic expressions for constant acceleration motion, we have

and

Eliminating the time \(t\) from these two expressions, we obtain

Experimental Procedure#

Procedure Preview#

OVERVIEW

Experimentally determine initial exit velocity of the metal ball (i.e. projectile) with two different experiments.

Ballistic Pendulum - Investigate how energy is converted and momentum is conserved:

Potential energy at the top and kinetic energy at the bottom.

Momentum after the collision and momentum before the collision.

Projectile Motion - Investigate kinematic motion for comparison.

Each experiment will have a total of 15 trials:

Groups of 2 students, each student will launch the projectile for 7 – 8 trials.

Groups of 3 students, each student will launch the projectile for 5 trials.

Additional Tips

The accepted value of \(g = 9.803\,\text{m/s}^2\) for Fairfield, CT.

Demo of the procedure is found in Demo Video: Ballistic Pendulum & Projectile Motion Experiment.

Demo Video: Ballistic Pendulum & Projectile Motion Experiment#

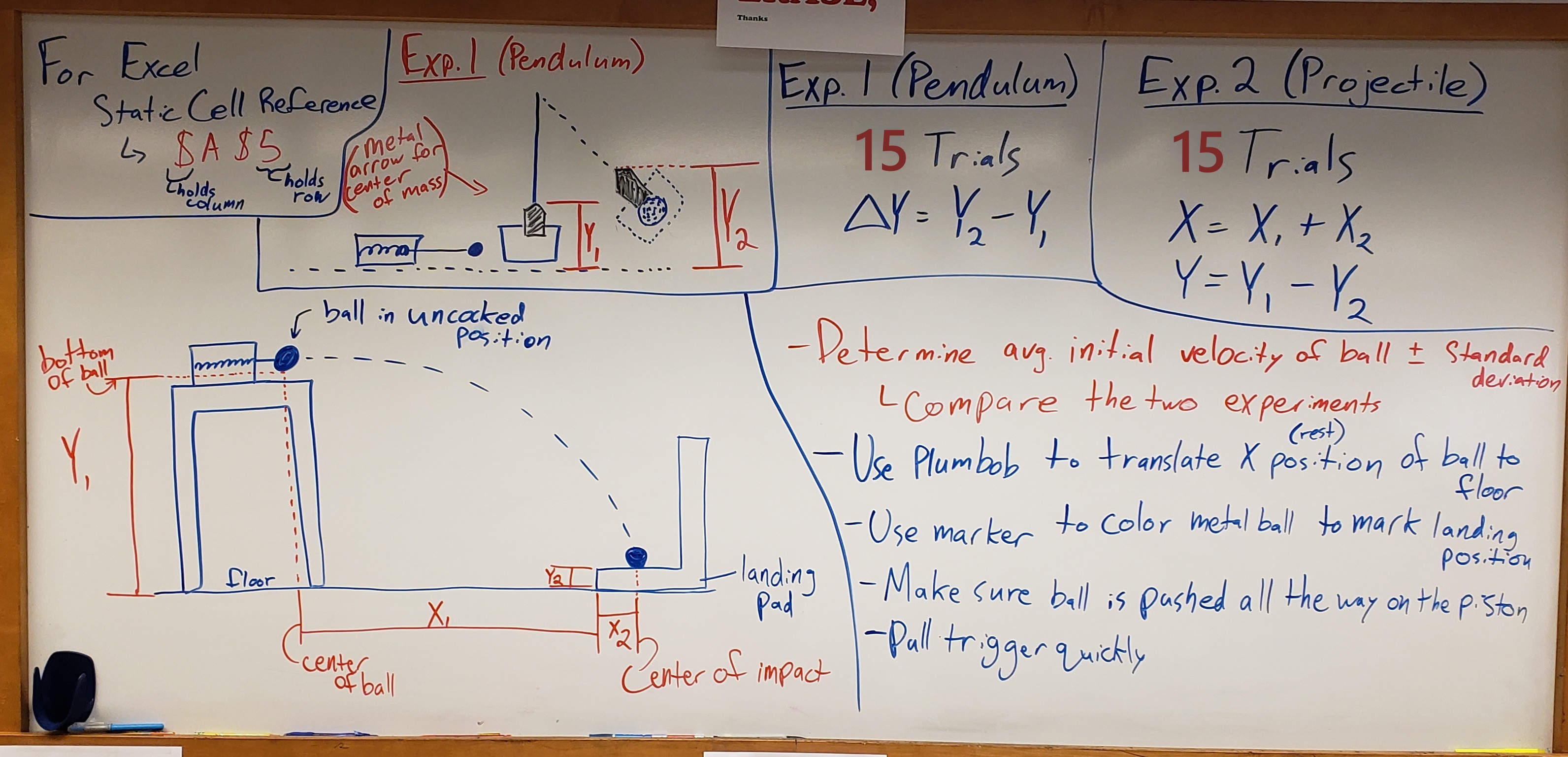

Ballistic Pendulum Experiment#

OVERVIEW — Ballistic Pendulum Experiment

Determine the initial exit velocity of the ball using conservation of energy and conservation of momentum.

Ballistic Pendulum — Preliminary Setup#

Create a common data table including (but not limited to):

accepted value of \(g\) of \(9.803\,\text{m/s}^2\) for Fairfield, CT

\(m\): mass of the ball (i.e. projectile)

\(M\): mass of the pendulum

\(y_1\): initial pendulum height

Set up the projectile motion experiment as shown in Fig. 46 and Fig. 47. Review the first half of the demonstration video Demo Video: Ballistic Pendulum & Projectile Motion Experiment.

Measure and record the mass \(m\) of the brass ball projectile.

Record the mass \(M\) of the pendulum that is indicated on the apparatus base plate (DO NOT REMOVE THE ARM).

DO NOT REMOVE THE ARM

Mass is written on the apparatus base plate.

Measure and record \(y_1\). The pointer on the side of the bob indicates the center of mass of the pendulum. With the pendulum hanging motionless, measure the height from the base plate (saying the base plate is our zero-point for the height) to the metal pointer on the pendulum bob as illustrated in Fig. 47.

Ballistic Pendulum — Data Collection#

Create a data table with enough rows for the number of trials you are doing along with average and standard deviations; include columns for each of the variables you will be measuring or deriving including, but not limited to:

Trial number

Lab member’s initials

\(y_2\): final pendulum height

\(\Delta y\): change in height of the combined pendulum and projectile

\(V\): initial pendulum velocity of the combined pendulum and projectile

\(v_{0\text{,ballistic-pendulum}}\): initial exit velocity of the ball

⚠️⚠️⚠️ CAUTION: HIGH SPEED PROJECTILES AND PISTON ⚠️⚠️⚠️

Keep clear of the pendulum and piston when spring-loaded gun is cocked. Fingers can be crushed.

Practice the following steps before actually taking data.

Place the brass ball on the pin of the gun, and press the ball so the spring of the gun is compressed until the trigger catches and holds the compressed spring. Loading launcher might require full body weight, hold on to the ball and slowly lean back.

Ensure the pendulum is stationary.

Ensure the ball is fully pushed onto the piston.

Fire the gun by squeezing the trigger with CONVICTION (quickly) to ensure more consistent firings. The ball will be captured by the brass bob and the pendulum will swing upwards.

A small ratchet on the bottom of the pendulum will tick up a rack that will capture the maximum upswing position of the pendulum.

Ball Falls Out After Collision? Make Sure To AIM

Sometimes the ball may not stay in the pendulum. Repeat the trial. If it continues falling out, the apparatus may need adjusting. Please ask for assistance.

There is some side-to-side play in the pendulum itself; when firing, line yourself up with the piston and check that the pendulum bob is lined up with the piston.

Measure the height \(y_2\) between a similar zero-height location to the tip of the metal pointer on the pendulum as illustrated in Fig. 47.

Carefully release the ratchet on the bottom of the pendulum so the pendulum can swing back to its equilibrium position. Do not twist or slide the pendulum off the rack, use the little handle on the spring loaded ratchet beneath the brass bob.

Release the ball from the bob of the pendulum by pushing it with your finger, a pencil, or other short cylinder.

Calculate \(\Delta y = y_2 - y_1\), the change in height.

Determine the initial velocity \(V\) of the combined pendulum and ball by going backwards through the sequence of events. Use the conservation of and change in energy from kinetic to gravitational potential energy during the upward swing (see (64) and (65)).

Determine the initial exit velocity \(v_{0\text{,ballistic-pendulum}}\) of the ball by going further backwards in the sequence of events. Use conservation of momentum to analyze the momentum of the pendulum and ball combination after the collision vs. the momentum of just the ball before the collision (see (66)).

Discussion Point: Sources of Error

During the sequence of the launch, collision, and upward swing:

What do you expect to be conserved or not conserved?

What physical processes may affect your results?

What are your measurement uncertainties?

After you double-check your methodology and that calculations are accurate in Excel and complete, repeat the steps in Ballistic Pendulum — Data Collection for the rest of your trials.

Ballistic Pendulum — Data Summary and Error Propagation#

If you haven’t already, add rows for average and standard deviation calculations.

Calculate the average and standard deviations of your measured and determined quantities across all experimental trials.

Using one of your trials, propagate your measurement uncertainties to see how your initial exit velocity might change (you could copy and paste it as a “test” trial at the bottom of your data table).

Note how individual quantities affect the initial exit velocity — does any specific quantity affect more than the others?

Note how the initial exit velocity changes (becoming faster or slower) when you consider all quantities exaggerated by their uncertainties.

Projectile Motion Experiment#

OVERVIEW — Projectile Motion Experiment

Determine the initial exit velocity of the ball using kinematics.

Projectile Motion — Preliminary Setup#

Add necessary common quantities to your common data table including (but not limited to):

\(y_1\): initial height from the bottom of the ball to the floor

\(y_2\): final height from the landing pad to the floor

\(Y\): total vertical distance traveled from bottom of ball to top of landing pad

\(x_1\): distance from bottom of the ball (uncocked) to the front edge of the landing pad

Set up the projectile motion experiment as shown in Fig. 48. Review the later half of the demonstration video Demo Video: Ballistic Pendulum & Projectile Motion Experiment.

Measure and record initial height \(y_1\) (see Fig. 48). This is the height from the bottom of the brass ball (i.e. projectile) to the floor.

Measure and record final height \(y_2\), effectively the thickness of the landing pad.

Determine total vertical distance traveled \(Y\).

Measure horizontal distance \(x_1\). Use a plumb bob to transpose the position of the center of the ball to the floor, and measure to the edge of the landing pad.

Projectile Motion — Data Collection#

Create a data table with enough rows for the number of trials you are doing along with average and standard deviations; include columns for each of the variables you will be measuring or deriving including, but not limited to:

Trial number

Lab member’s initials

\(x_2\): distance of impact from the edge of the landing pad

\(X\): total horizontal distance traveled from center of ball when uncocked (at initial release position) to center of impact

\(v_{0\text{,projectile-motion}}\): initial exit velocity of the ball

⚠️⚠️⚠️ CAUTION: HIGH SPEED PROJECTILES AND PISTON ⚠️⚠️⚠️

DO NOT BE DOWN RANGE OF LAUNCHER — stand off to the side to keep from being hit.

Keep clear of the pendulum and piston when spring-loaded gun is cocked. Fingers can be crushed.

Practice the following steps before actually taking data.

Ensure the pendulum is resting on the ratchet rack and out of the way.

Place the brass ball on the pin of the gun, and press the ball so the spring of the gun is compressed until the trigger catches and holds the compressed spring. Loading launcher might require full body weight, hold on to the ball and slowly lean back.

Using a dry-erase marker, mark up the edges of the ball such that it will leave a mark on the landing pad.

Ensure the ball is fully pushed onto the piston.

Fire the gun by squeezing the trigger with CONVICTION (quickly) to ensure more consistent firings. The ball will impact the landing pad and leave a dot from the dry-erase marker.

Measure the distance \(x_2\) from the edge of the landing pad to the center of the impact mark as illustrated in Fig. 48.

Calculate \(X = x_1 + x_2\), the total horizontal distance traveled.

Determine the initial exit velocity \(v_{0\text{,projectile-motion}}\) of the ball by using kinematics (see (67) to (69)).

Discussion Point: Sources of Error

During the sequence of the launch and projectile motion:

What do you expect to be conserved or not conserved?

What physical processes may affect your results?

What are your measurement uncertainties?

After you double-check your methodology and that calculations are accurate in Excel and complete, repeat the steps in Projectile Motion — Data Collection for the rest of your trials.

Clean up

Once you’re finished with the projectile motion launches, wipe off the marker from the ball, thanks.

Projectile Motion — Data Summary and Error Propagation#

If you haven’t already, add rows for average and standard deviation calculations.

Calculate the average and standard deviations of your measured and determined quantities across all experimental trials.

Using one of your trials, propagate your measurement uncertainties to see how your initial exit velocity might change (you could copy and paste it as a “test” trial at the bottom of your data table).

Note how individual quantities affect the initial exit velocity — does any specific quantity affect more than the others?

Note how the initial exit velocity changes (becoming faster or slower) when you consider all quantities exaggerated by their uncertainties.

Experiment Comparison#

Create a summary table to summarize the results from both experiments including the average and standard deviations of the initial exit velocities of the ball from both experiments (i.e. avg. and std. dev. of \(v_{0\text{,ballistic-pendulum}}\) and \(v_{0\text{,projectile-motion}}\)).

Trust?

Considering both experiments, do your results agree with each other?

Since we don’t have an accepted or “true” value for the ball’s initial exit velocity, which experiment do you trust more — consider the errors, uncertainties, and physical processes and assumptions from each experiment.

Post-Lab Submission — Interpretation of Results#

Make sure to submit your finalized data table (Excel sheet).

In a paragraph, summarize your error analysis. Be qualitative not only quantitative.

What is the precision of your equipment?

What are possible random errors for today’s experiment?

What are possible systematic errors for today’s experiments?

What are the effects of your measurement uncertainties on your determined exit velocities for both experiments?

In a paragraph, summarize the results you have determined in each case. Consider:

What were your initial exit velocity results for both pendulum and projectile experiments? Use your average values and treat your standard deviations as your \(\pm\) uncertainty of those average values.

Do the initial velocities from both experiments agree with one another?

How and why are they (or could be more) different regarding physical concepts?

Considering both experiments and their sources of error, which experimental exit velocity do you trust more? Explain your answer using both physical concepts and your error propagation.

Suppose you would have used a more massive marble in the projectile motion portion of the experiment. How would this affect your result? Explain your answer using a physics argument.

The Whiteboard#