Electrical Example of an Exponential Decay Process with Resistors & Capacitors (RC Circuits)#

Background#

Overall goals and overview#

Understand what a capacitor is, the relationship between capacitance and resistance, the discharging nature of capacitors

Assume we know the resistance of your resistors, but we don’t know the capacitance of the capacitors, and we need to determine those C values

DISCUSSION POINT: How do different RC (resistor-capacitor) combinations affect the change of their circuits’ voltages over time?

Conduct two experiments:

Measure the capacitance of your capacitors, \(C_1\), \(C_2\), and \((C_1+C_2)\)

GRAPHICALLY with LN(V) vs. Time plot (a linearized version of exponential decay plot)

Via the HALF-LIFE, \(t_{1/2}\) (where half-life, the time for exponential decay to reach half its original value, is related to the natural log of 2 [LN(2)])

Divide charge between two capacitors

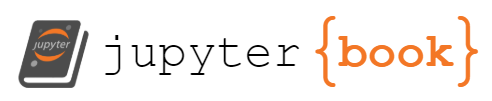

There are many processes in which the rate of change of a quantity is proportional to the magnitude of the quantity itself. The result is a quantity that is an exponential function of time. In this experiment the characteristic exponential relaxation (decay) of the voltage or charge on a capacitor will be investigated. The electrical analogy of this general process can be represented by a simple circuit in which a capacitor is allowed to discharge through a resistor connected across its terminals. Consider the schematic circuit of Fig. 92.

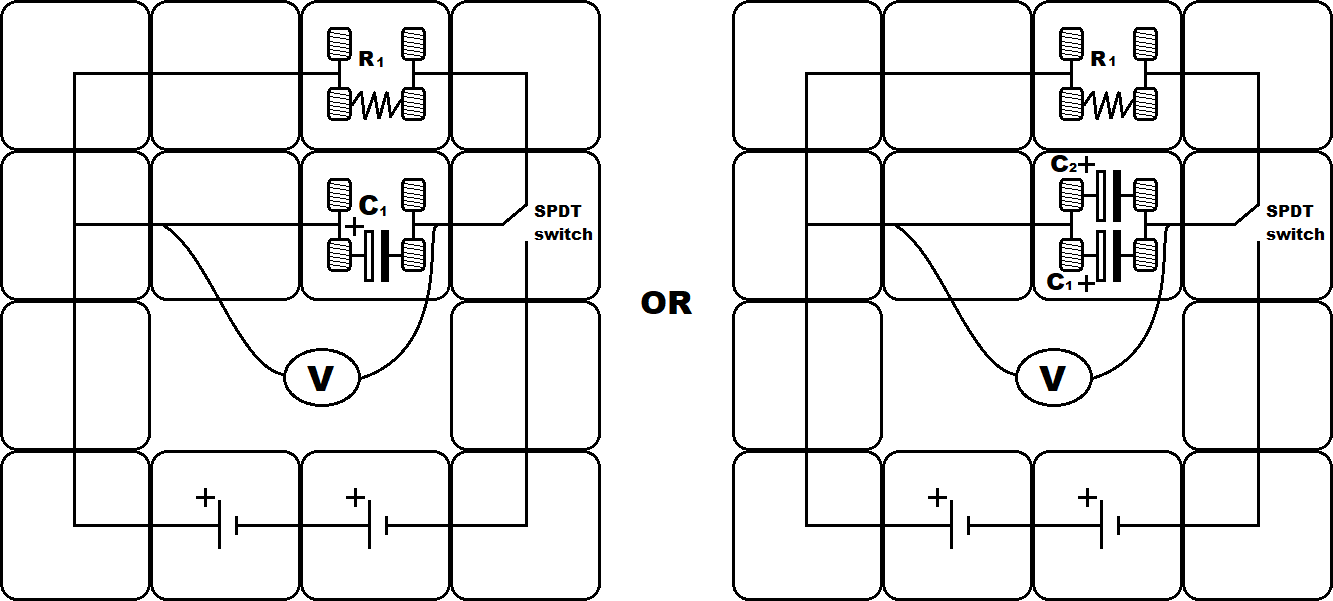

Fig. 92 Schematic of RC circuit charging the capacitor.#

With the switch connecting the capacitor to the batteries, the capacitor rapidly charges up to the potential of the batteries. Since a capacitor will not pass a DC current, a positive charge builds up on one of the plates while a negative charge forms on the other. When the switch is flipped to connect the capacitor to the resistor, we have the circuit (shown below) containing a charged capacitor with a resistance across its terminals. We will now investigate how the voltage across the capacitor changes with time, starting at \(t = 0\) when the capacitor is fully charged. The voltage will be measured by the voltmeter \(V\) connected as shown. As time progresses, current will flow from the positively charged plate of the capacitor through the resistance \(R\) to the negatively charged plate.

Fig. 93 Schematic of RC circuit disconnected from the battery.#

Since a voltage exists across the capacitor, there must also be a voltage across \(R\). This implies an electric current, and from Ohm’s Law:

Since current is a flow of charge, \(Q\), and since the two sides of the capacitor are isolated from each other, the charge which flows through the resistor must originate on one of the plates and terminate on the other. Thus the flow of current reduces the charge on the capacitor. In a time, \(t\), the amount of charge that passes through the resistor is \(I \times t\). This must be \(-Q\) (the negative change in the charge on the capacitor) which leads to the relation:

The value of the resistance limits the amount of current that can flow and thus limits the rate of discharge of the capacitor.

From the definition of a capacitor, we know that the larger the voltage applied to the capacitor, the more charge it will put on the capacitor. Hence, if \(V\) is the voltage across the capacitor, then \(Q\) is proportional to \(V\). The larger the plate area, the more charge it should hold. In addition, if the plates are brought closer together, the positive plate will attract more negative charge from the battery to the negative plate. All these factors have to do with the geometry and construction details of the device. Thus, the bigger the plate area and the smaller the plate spacing, the larger the charge that accumulates in the capacitor for a given voltage. Hence we can write:

where \(C\) is a constant for a given capacitor called its capacitance.

Combining these three equations, we obtain:

Notice that the rate of change of the charge at any time is directly proportional to the amount of charge on the capacitor at that time. (This is similar to the amount of radiation given off by a quantity of decaying atoms.) By writing (124) in the form:

both sides of the equation can be integrated to obtain:

After some simplification, the solution to this differential equation is:

At \(t=0\), \(V = V_{0}\), so that \(Q = CV_{0}\) for \(t = 0\). Thus the behavior of \(Q\) or \(V\) is the same after the switch is opened:

The behavior of the current \(I\) is found directly from this:

The product \(RC\) has the units of time (Ω × F); we can verify this by using dimensional analysis:

This product is called the time constant of the circuit. In a time equal to \(RC\), the voltage, \(V\), drops to a fraction:

This means that in any interval of time equal to \(RC\), the voltage has decreased to 36.8% of the initial value. In determining \(RC\), it is often more convenient to measure the time for the voltage to drop to \(\frac{1}{2}\) of its initial value and from this to compute \(RC\). The “half-life,” \(t_{1/2}\), is given by:

Taking the natural logarithm of both sides and simplifying we obtain:

or

Note that by taking the natural log of the expression for the voltage, (125), we obtain:

If we plot the value of the natural log of \(V\) as a function of time, \(t\), we obtain a straight line whose slope is \(-1/RC\) with an intercept of \(\ln V_{0}\). From this slope, we can obtain a measured value for the product \(RC\) which is the time constant, i.e. the time it takes the voltage (or charge) to decay to \(1/e\) of its original value (see (126)).

Dividing charge across capacitors#

A capacitor \(C\) at voltage \(V\) holds a charge \(Q = CV\). In the circuit shown in Fig. 97 when the single-pole-double-throw switch connects the first capacitor to the voltage source, it holds a charge \(Q_1 = C_1 V\). The switch is then flipped to disconnect the capacitor from the battery and connect it to the second capacitor. Charge moves from the first capacitor to the second, lowering the voltage. Assuming the second capacitor is initially uncharged, the total charge is unchanged. The total charge must be divided between the two capacitors so that they come to the same lower final voltage:

Because the two capacitors are at the same voltage, the total charge is divided between them in proportion to their capacitance.

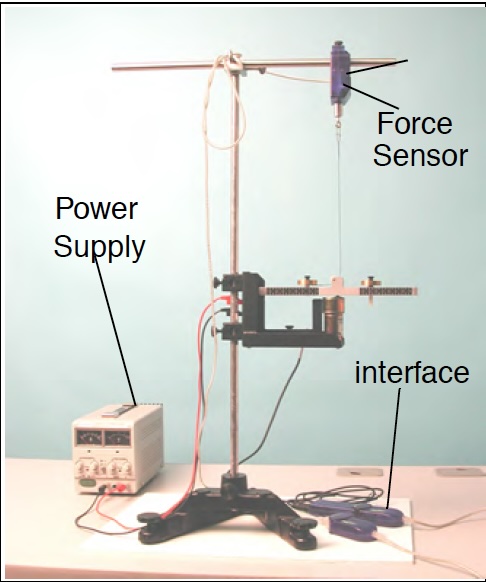

Fig. 94 Left) Modular electronic RC circuit. Right) Wire, 2 capacitors, 2 resistors.#

Equipment#

The general setup can be seen in Fig. 94, with the voltmeter attached on either side of the capacitor section of the circuit.

Two known (with ohmmeter) ceramic resistors

Pasco modular circuit kit

4× Circuit corners

1× Circuit T-conjunction

4× Circuit straights

2× AA battery module

2× Spring clips (to attach individual resistors or capacitors)

1× Single-pole double-throw (SPDT) switch to open and close circuit during reconfiguration, charging of capacitors, and discharging of capacitors through resistors

15× U-shaped jumper clips to connect the different modules

1× Voltmeter via Capstone – connected to the jumper clips the on either side of the capacitors with alligator clips

Fluke multimeter with alligator clips

Use as Ohmmeter (Ω) to measure resistors’ resistance to be treated as known values

Use as capacitance meter (F) to measure capacitors’ actual capacitance to compare experimental values to later on

Experimental Procedure#

FIRST EXPERIMENT We study resistor-capacitor circuits and how capacitors discharge.

You have two resistors and two capacitors. Create a common data table and measure the value of resistors \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) with the Fluke multimeter set to measure ohms (Ω, note the units on the multimeter). [It doesn’t matter which resistor is which number, just be consistent] Also in the common data table, record the actual capacitance of \(C_1\), \(C_2\), and the parallel combination of \((C_1+C_2)\) with the Fluke 175 multimeter when set to measure farads (the yellow alternate function of the ohmmeter, looks like two letter T’s that are rotated toward each other).

Use the capacitors with individual resistors. Perform the following steps for the following pairs of resistor and capacitor cases:

\(R_1+C_1\)

\(R_2+C_1\)

\(R_1+C_2\)

\(R_1+(C_1+C_2)\) in parallel

\(R_1+(C_1+C_2)\) in series

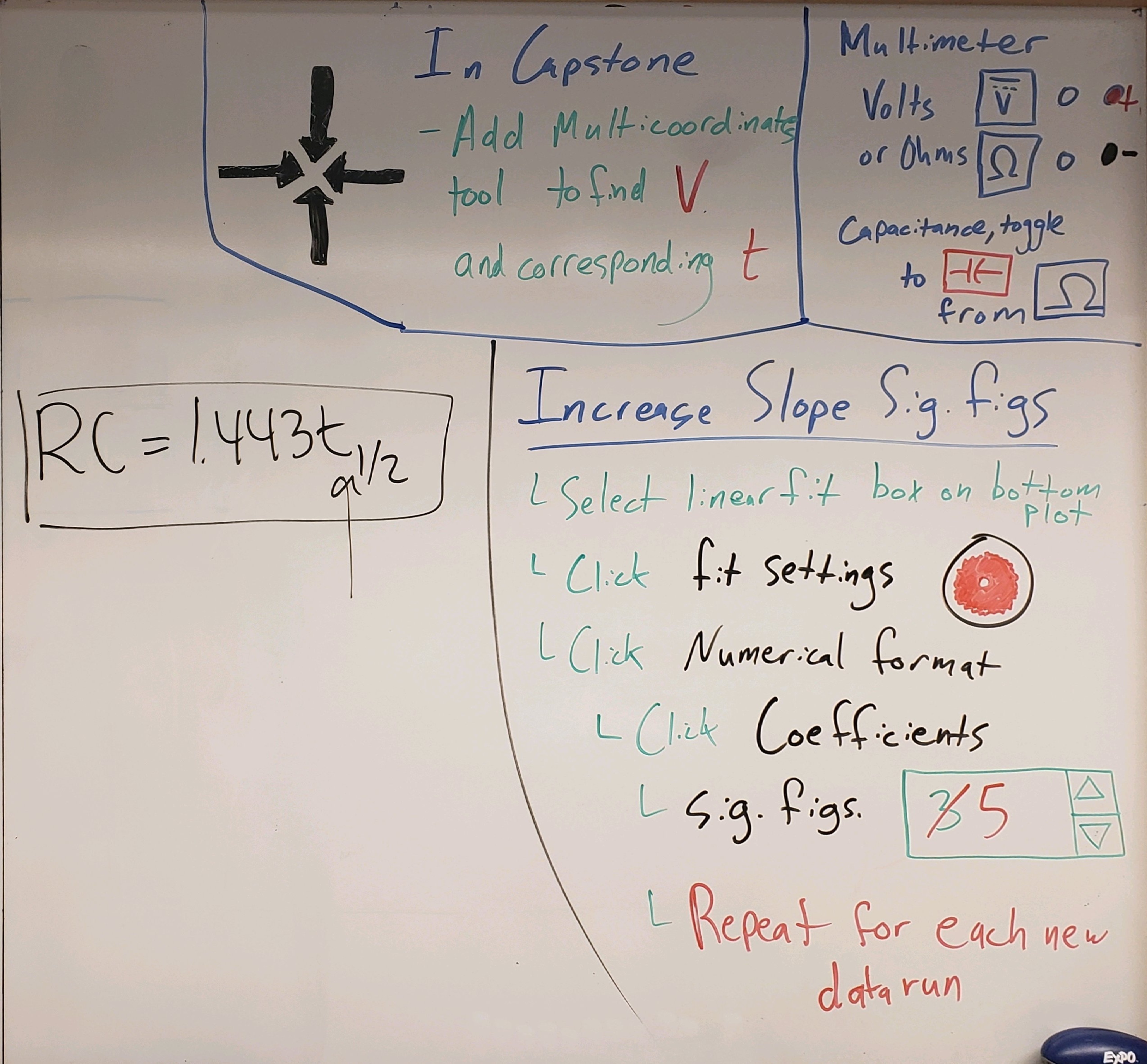

Zero the voltage sensor (this is before any resistors or capacitors are in the circuit). Connect the voltmeter to the Capstone program via the PASCO 850 Universal Interface. Set the sample rate to 2500 samples per second (should be set by default, double check though). Zero the voltage sensor in Capstone by first opening the single-pole-double-throw (SPDT) switch to ensure no current is flowing; then in the bottom recording bar, with the voltage sensor selected, click the zero button (zero with two yellow arrows pointing towards each other).

In Capstone (should be already set up), you should have graphs of the voltage versus time, the Natural Log(V) vs. time, and a running table of voltages and times (this table is connected to the V vs. T plot, so if you highlight data points on the plot, they’ll be highlighted in the table).

Fig. 95 Modular electronic RC circuit. The resistors and capacitors will just be placed in the spring modules to become part of the circuits. Left) Example with one resistor and one capacitor. Right) Example with one resistor and two capacitors.#

Connect the resistor, capacitor(s), switch, batteries, voltmeter as shown in Fig. 95.

Create a data table for the first resistor and capacitor case (once you have this all set up, you’ll then be able to just copy and paste this data table for the five other RC combinations):

With five columns (1 for each of the 5 decay trials, the act of discharging each capacitor). Also include a column for the average values, a column for the standard deviation (σ), and a column for the standard error of the mean (\(\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n-1}}\) where \(n=\) number of trials. Reminder, this is effectively your +/- uncertainty of the average. DISCUSSION POINT for later: How well does your average value of capacitance +/- standard error agree with your expected values?).

Include three rows for:

Slope. You will get this from the linear fit of the natural log(V) vs. time plot (linearizing the exponential decay) in Capstone where the fit will be in the form \(Y=mt + b\), and slope \(m=\frac{-1}{RC}\))

Time constant \((RC)\) of the exponential decay as determined from the slope

Capacitance (\(C_{\text{graphically from decay}}\)) as determined from the decay time constant

Include an additional six rows for:

Initial voltage (\(V_{\text{init}}\), right after decay starts)

Final voltage (\(V_{\text{final}} = V_{\text{init}}/2\), i.e. voltage that is half the value of the initial voltage)

Initial time (\(t_{\text{init}}\), when \(V=V_{\text{init}}\)). Found either with the Capstone table or the individual data point selection tools

Final time (\(t_{\text{final}}\), when \(V=V_{\text{final}}\)). Found in a similar way in Capstone, just at half the voltage

Half-life (\(t_{1/2}= t_{\text{final}}-t_{\text{init}}\))

Capacitance (\(C_{\text{by half-life}}\)) as determined by the rearrangement of (128) (the characteristic of the half-life of an exponential decay)

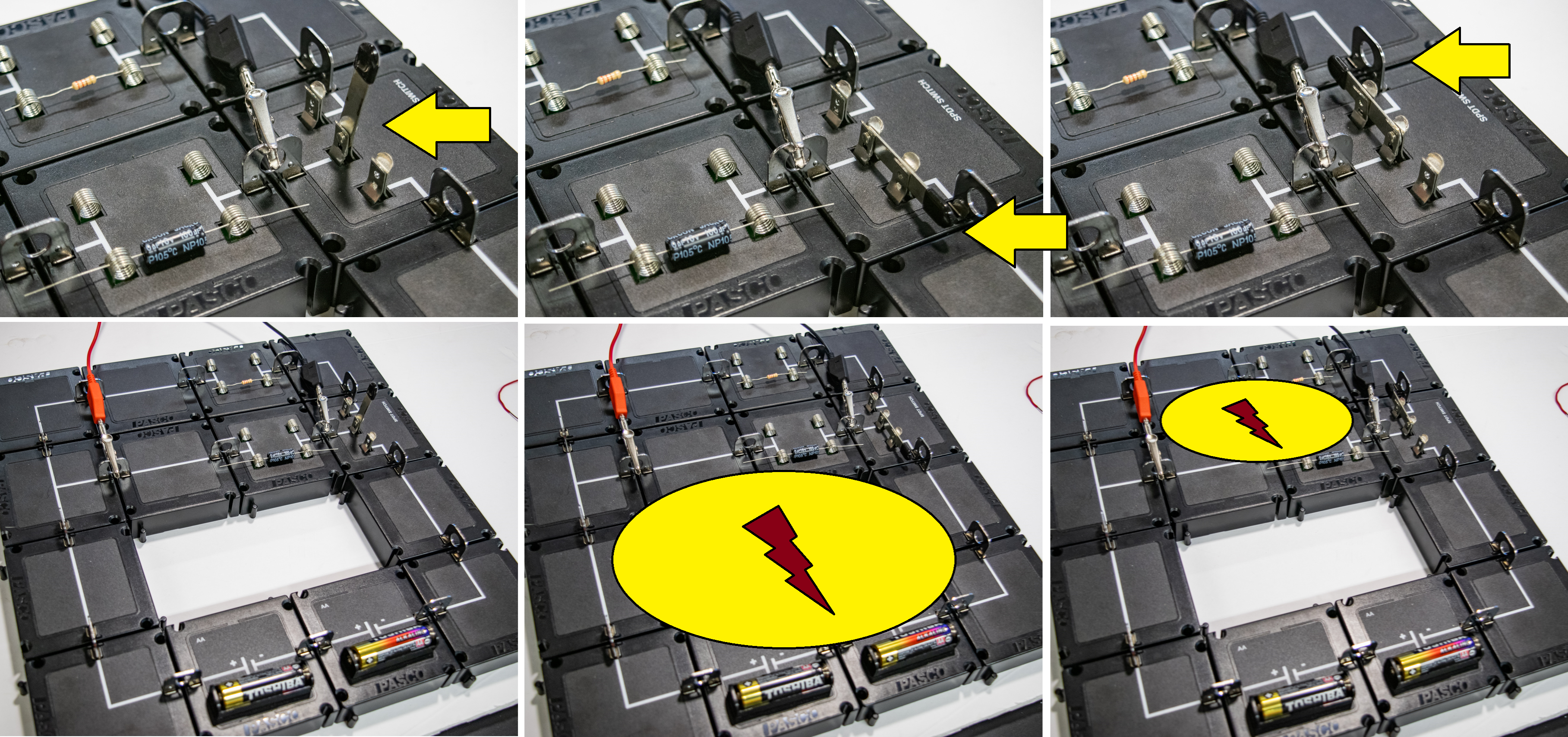

Fig. 96 Top) SPDT switch in different positions. Bottom) Whole circuit with the SPDT switch in the respective positions. Left) Open circuit. Center) Charging central capacitor; current flows in lower portion of the modular circuit. Right) Discharging either through resistor (or for Experiment 2, charging the other capacitor); current flows in upper portion of the modular circuit.#

DATA TAKING:

Start recording; flip the SPDT switch to connect the batteries to the capacitor and observe the voltmeter as the capacitor rapidly charges to \(V_{ ext{init}}\). Once the capacitor is fully charged (voltmeter shows constant voltage at \(V_{ ext{init}}\)), flip the switch to connect the capacitor to the resistor; observe the decay of the voltage across the capacitor. Wait until the voltage drops to less than 10% of \(V_{ ext{init}}\). (e.g. if \(V_{ ext{init}}=3.0\) V, then \(V_{ ext{minimum}}= 0.3\) V) In essence, the battery has been eliminated from the circuit and the capacitor is now acting as the voltage source.

WHILE STILL RECORDING: (so everything is just in the same plot, save some time) Repeat this switch flipping four more times for a total of 5 decays.

GRAPHICAL: In the Capstone plot of LN(Voltage) vs. Time, highlight the data of the linear portion of the decay curve with the highlighter tool and record the slope. The linear section covers the time it took voltage to decay from 100% to 10% of \(V_{ ext{init}}\). The linear fit, as described in (129), in Capstone should be in the form \(Y=mt + b\), where \(m=\frac{-1}{RC}\). Calculate the time constant \(RC\), and the capacitance \(C_{ ext{graphically from decay}}\) as determined from that time constant.

HALF-LIFE: Find the voltage and time of when your capacitor was at its initial voltage right before decay. Divide the \(V_{ ext{init}}\) by 2 to find the final voltage; then find the time for that final voltage. Determine half-life from the time difference (\(t_{1/2}= t_{ ext{final}}-t_{ ext{init}}\)). Suggestions on finding those values: Examine the exponential decay plot (V vs. T) with the crosshair tool by zooming in to find the data points right before the voltage decay, clicking the data point and selecting the crosshair, then note the time and voltage. Alternatively, in the exponential decay plot (V vs. T), zoom in to the area right before decay and use the data highlight tool to make a small selection box which will then also highlight those same data points in the Capstone table of voltages and times.

For your capacitance that you determined graphically from the LN(V) vs. time slope, calculate the average, standard deviation, and standard error of the mean. For your capacitance that you determined with the half-life \(t_{1/2}\) (time span for initial voltage to halve), determine the standard deviation (σ) and standard error of the mean (\(\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n-1}}\)).

\pagebreak \item DATA TAKING: \vspace{-2mm} \begin{itemize} \label{E4_procedure_6} \item Start recording; flip the SPDT switch to connect the batteries to the capacitor and observe the voltmeter as the capacitor rapidly charges to \(V_{\mbox{init}}\). Once the capacitor is fully charged (voltmeter shows constant voltage at \(V_{\mbox{init}}\)), flip the switch to connect the capacitor to the resistor; observe the decay of the voltage across the capacitor. \textbf{Wait until the voltage drops to less than} \(10\%~\text{of}~ V_{\mbox{init}}\). (e.g. if \(V_{\mbox{init}}=3.0~V\), then \(V_{\mbox{minimum}}= 0.3~V\)) In essence, the battery has been eliminated from the circuit and the capacitor is now acting as the voltage source. \item WHILE STILL RECORDING: (so everything is just in the same plot, save some time) Repeat this switch flipping \textbf{four more times} for a total of \textbf{5 decays}. \item GRAPHICAL: In the Capstone plot of LN(Voltage) vs. Time, highlight the data of the linear portion of the decay curve with the highlighter tool and record the slope. The linear section covers the time it took voltage to decay from 100% to 10% of \(V_{\mbox{init}}\). The linear fit, as described in Eqn.~\ref{E4Eq:16}, in Capstone should be in the form \(Y=mt + b\),~where~\(m=\frac{-1}{RC}\). Calculate the time constant \(RC\), and the capacitance \(C_{\mbox{graphically from decay}}\) as determined from that time constant. \item HALF-LIFE: Find the voltage and time of when your capacitor was at its initial voltage right before decay. Divide the \(V_{\mbox{init}}\) by 2 to find the final voltage; then find the time for that final voltage. Determine half-life from the time difference (\(t_{1/2}= t_{\mbox{final}}-t_{\mbox{init}}\)). \textit{Suggestions on finding those values}: Examine the exponential decay plot (V vs. T) with the crosshair tool by zooming in to find the data points right before the voltage decay, clicking the data point and selecting the crosshair, then note the time and voltage. Alternatively, in the exponential decay plot (V vs. T), zoom in to the area right before decay and use the data highlight tool to make a small selection box which will then also highlight those same data points in the Capstone table of voltages and times. %\item Then repeat this step \textbf{four more times} for a total of \textbf{five time trials}. \end{itemize}

\vspace{-2mm}

\item \begin{itemize}

\item For your capacitance that you determined \textit{\textbf{graphically}} from the LN(V) vs. time slope, calculate the average, standard deviation, and standard error of the mean.

\item For your capacitance that you determined with the \textbf{\textit{half-life}} $t_{1/2}$ (time span for initial voltage to halve), determine the standard deviation ($\sigma$) and standard error of the mean ($\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n-1}}$).

\end{itemize}

Compare this value for capacitance to the actual capacitance values of the capacitors, \(C_1\), \(C_2\), and \((C_1+C_2)\) you measured with the multimeter in Step 2.

Replace the resistor and/or capacitor for the next combination and repeat the procedure (from Step 7) above for each of the six combinations listed in Step 2.

DISCUSSION POINT: How do different RC (resistor-capacitor) combinations affect the change of their circuits’ voltages over time (i.e. decay)?

DISCUSSION POINT: How well does your average value of capacitance +/- standard error agree with your expected values? Why or why not? What are possible sources of uncertainty or systematic bias that could cause your values to agree/not agree with your expected values that you had found with the multimeter?

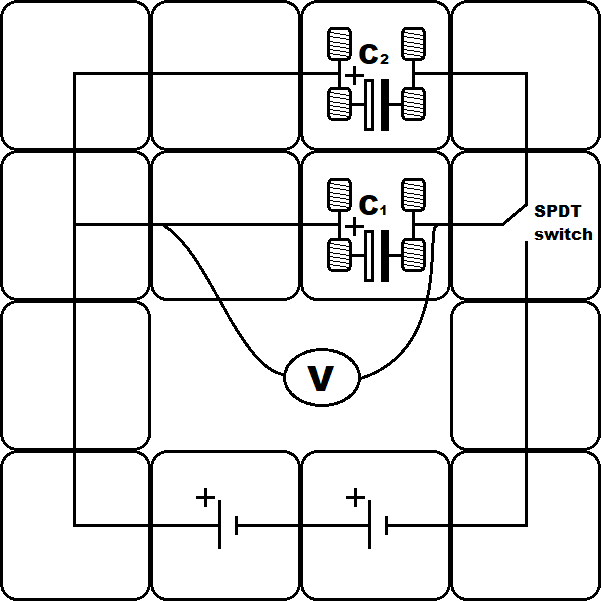

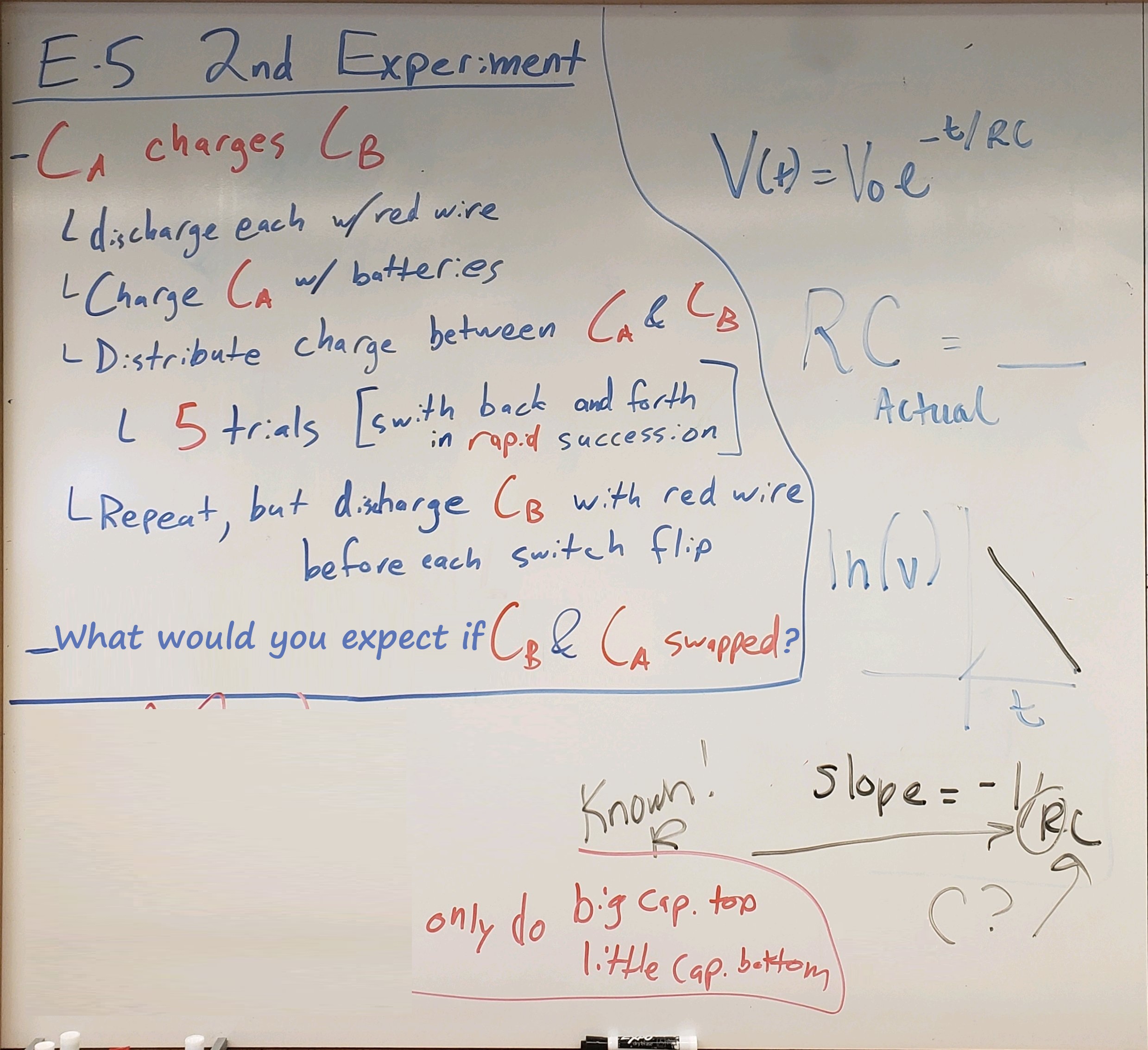

SECOND EXPERIMENT We study dividing charge across two capacitors, as in Fig. 97.

\vspace{-3mm}

Fig. 97 Modular electronic circuit with two capacitors.#

Ignore what you’ve called the capacitors from the first experiment, now just consider them as either low- or high-capacitance capacitors in either the \(C_1\) or \(C_2\) positions. Construct the circuit shown in Fig. 97 by replacing the resistor with the high-capacitance capacitor (in the top springs block, e.g. \(C_2\) position in Fig. 97). Put the low-capacitance capacitor in the bottom springs block (\(C_1\) position in Fig. 97). Ensure the voltmeter is connected as in Fig. 97 and continue using the same Voltage vs. time plot in Capstone.

Create a data table including your previous, experimentally-determined values of capacitance of \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) and three columns for initial and final voltages as well as the difference between the two. Create five rows for five trials. Note: Initial voltage is V when the battery is connected to \(C_1\) before you throw the switch to connect the capacitors together in Step 5. Final voltage is V after you throw the switch to allow the charge in the first capacitors to be distributed between the two capacitors.

Temporarily connect a wire across each capacitor to discharge them before flipping the switch (i.e. no charge is stored and both circuits are open).

Connect \(C_1\) to the battery using the single-pole-double-throw (SPDT) switch. Record the initial voltage.

Flip the SPDT switch to disconnect \(C_1\) from the battery and connect it to \(C_2\). Flip the switch back and forth quickly for a total of five trials. Record the final voltage after the charge is distributed between the capacitors (near immediate change).

Notice how the final voltage is drifting up towards the initial voltage and the difference between the two is changing. Something is wrong with the assumptions built into (130) (which should be true). The problem is that after the first time throwing the switch, \(C_2\) is not at zero charge. So the total charge is higher than \(C_1 V\). Challenge: Can you figure out what the voltage will be after the second, third, or \(n\)th time you flip the switch?

Try temporarily connecting a wire across \(C_2\) to discharge it before flipping the switch. Now you should consistently get the final voltage predicted by (130). Record the initial and final voltages after doing this five more times. Does this voltage difference agree with (130)?

Repeat from step 4 with the low- and high-capacitance capacitors in swapped positions in the circuit.

Post-Lab Submission — Interpretation of Results#

Make sure to submit your finalized data sheet with summarized data and cleaned-up plots (Excel sheet)

Paragraph of your results +/- uncertainties from your data. Make sure to include discussion of the following:

Do your experimental results for average capacitance agree with your expected values (as measured with the multimeter)?

Is the graphical or half-life method more accurate to the expected values; why?

How do different RC (resistor-capacitor) combinations affect the change of their circuits’ voltages over time (i.e. decay)?

Explain why, in step 3 of the second experiment you connect a wire across each capacitor. Why is a brief connection sufficient? Hint: What is the time constant for the wire and capacitor; how is it different to the resistor and capacitor setup?

Paragraph of your errors and estimated measurement uncertainties. Be quantitative. Make sure to include discussion of the following:

Where might systematic (affecting accuracy) and/or random (affecting precision) errors be coming from?

What are your measured uncertainties, and, based on these uncertainties, how do your final results change? I.e. do your different measurement and slope uncertainties make your final results larger or smaller?

If larger or small, are they more or less accurate to expected values?

How could you improve your random errors?

Were your systematic errors significant; how could this be improved if you were to re-run this experiment?

Reflect on this week’s lab; what did you learn?

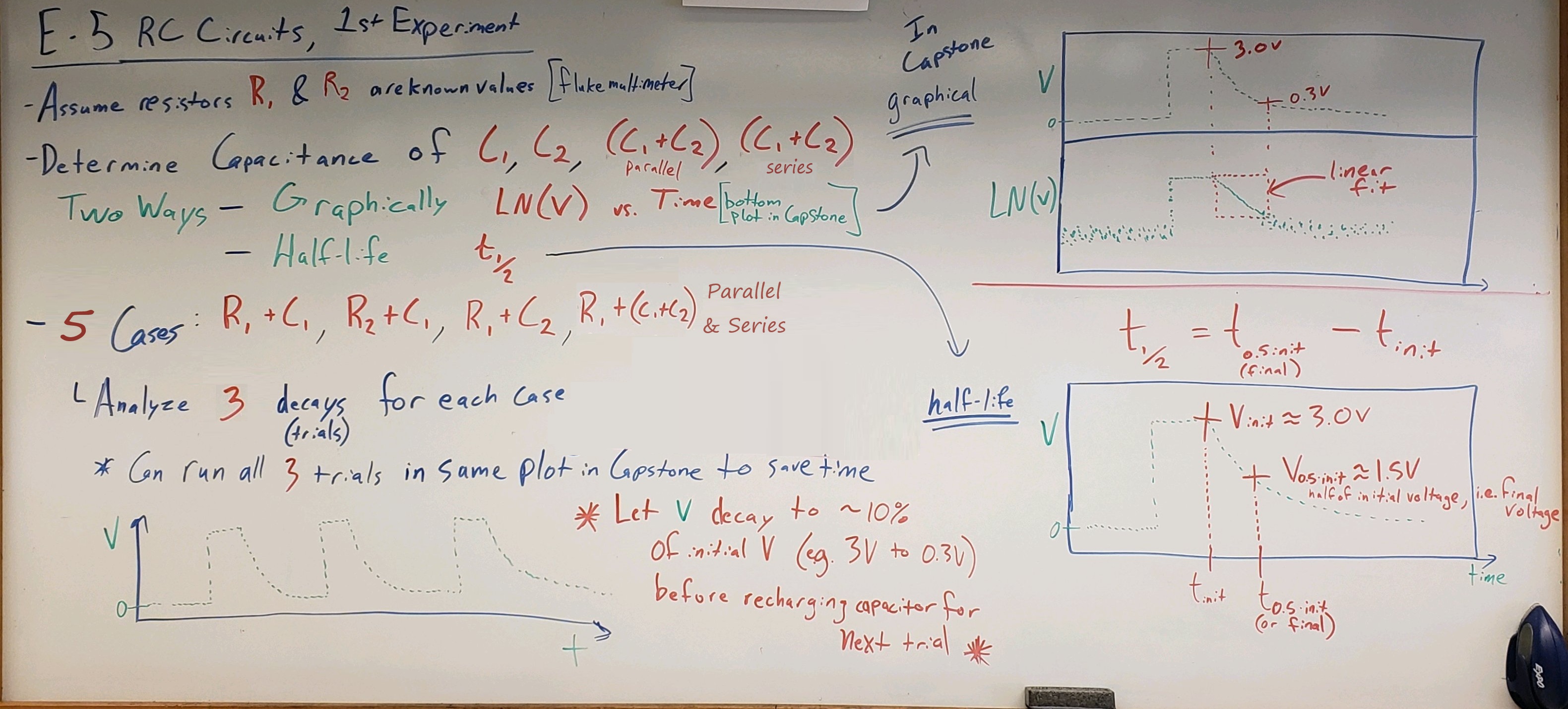

The Whiteboard#

Fig. 98 Overview 1st part.#

Fig. 99 Overview 2nd part.#

Fig. 100 Multimeter settings; Capstone significant figures notes.#