Resistivity with Resistors & DC Circuits#

Background#

Overall goals and overview#

Investigate the relationship between resistance, voltage, and current within a circuit as well as Ohm’s Law.

Conduct three experiments covering circuits with resistors and light bulbs, resistors in series, and resistors in parallel. You will apply a range of voltages through the circuits and measure both current and voltage across the resistors and light bulbs individually and compare your experimental resistances to the “actual” resistance as measured with the ohmmeter. You will then apply just 4.00 V to the circuit with all three resistors in either series or parallel configurations and again measure both current and voltage across each resistor and compare to the expected values

If a potential difference \(V\) is applied across some element in an electrical circuit, the current \(I\) in the element is determined by a quantity known as the resistance \(R\). The relationship between these three quantities serves as a definition of the quantity resistance \(R\):

An object that is a pure resistor has its total electrical characteristics determined by (122). Other circuit elements may have other important electrical characteristics in addition to resistance, such as capacitance or inductance. The resistance of any circuit element, whether it has other significant electrical properties or not, is given by the ratio of voltage to current as described in (122). For any given circuit element, the value of this ratio may change as the voltage and current changes. Nevertheless, the ratio of \(V\) to \(I\) defines the resistance of the circuit element at that particular voltage and current. The unit of resistance is the volt/ampere defined as the ohm, denoted by the symbol “\(\Omega\).”

Certain circuit elements obey a relation that is known as \textbf{Ohm’s Law}. For these elements, the ratio of \(V\) to \(I\) (i.e.\ \(R\)) is a \textit{\textbf{constant}} for different values of \(V\). Therefore, in order to show that a circuit element obeys Ohm’s Law, it is necessary to vary the voltage (the current will then also vary) and observe that the ratio \(V/I\) is in fact \textit{constant}. In this experiment, such measurements will be performed on two different elements to determine their resistance (ceramic resistors and an incandescent light bulb).

The resistance of any object to electrical current is a function of the material from which it is constructed, as well as the length, cross-sectional area, and temperature of the object. At constant temperature, the resistance \(R\) of a sample with a constant cross-section \(A\), and length \(L\) is given by \begin{equation} R=\rho \frac{L}{A}, \end{equation} where \(\rho\) is a material constant called the resistivity. Normally \(\rho\) is dependent upon the temperature of the sample and depending upon the material, \(\rho\) may either increase or decrease with increasing temperature. Thus if the current is sufficient, the heating of the material by the current passing through it can change the resistance.

Consider a “black box” with some unknown circuit inside connected to two terminals on the box. If we apply a voltage \(V\) to the terminals and observe a current \(I\) flowing through the “black box,” we define the resistance of the “black box” to be \(R = V/I\). If the resistance of the circuit element is a constant independent of both the current and the voltage, then we say that the circuit element is ohmic and that it follows Ohm’s law. Georg Simon Ohm found that most pure metals at room temperature have this property. However, a light bulb has a tungsten filament that heats up as you increase the current through it. Since the resistance of tungsten increases with temperature, the resistance of the tungsten filament increases as the voltage increases. Therefore a light bulb does not follow Ohm’s law.

For an ohmic resistor, when a voltage \(V\) is applied, then the current is \(I = V/R\), so the current is proportional to the voltage. If you plot voltage vs. current, the result is a straight line whose slope is the resistance. For a non-ohmic element like a light bulb, a plot of voltage vs. current is curved.

Series and parallel circuits:

Fig. 87 Resistors connected in Series (top) and Parallel (bottom).#

Series and parallel connections for three resistors (\(R_1\), \(R_2\), \(R_3\)) are illustrated in Fig. 87.

The equivalent resistance \(R_{\text{eq}}\) for each of these networks is that resistance which can replace the network of resistors between the terminals of the network. \(R_{\text{eq}}\) for each is given by:

Notice that if a voltage is applied across the terminals of a series circuit, the current that flows is the same in all elements and the sum of the voltage across each element is equal to the total applied voltage. The relationship of the voltages is a statement of conservation of energy and is known as Kirchhoff’s Voltage Rule (a.k.a. Loop Rule). It is more commonly stated as “The algebraic sum of the voltage changes around any closed loop is zero.”

If a voltage is applied across the terminals of a parallel circuit, the voltage is the same across all the elements and the total current flowing into or out of the circuit is the sum of the currents through each of the elements. The relationship of the currents is a statement of conservation of charge and is known as Kirchhoff’s Current Rule (a.k.a. Junction Rule). It is more commonly stated as “The sum of currents into a junction = the sum of currents out of the junction.”

Kirchhoff’s Rules can be used to completely analyze a complex network of circuit elements. Their application will provide the necessary equations to calculate the current through and the voltage across all the elements of a circuit.

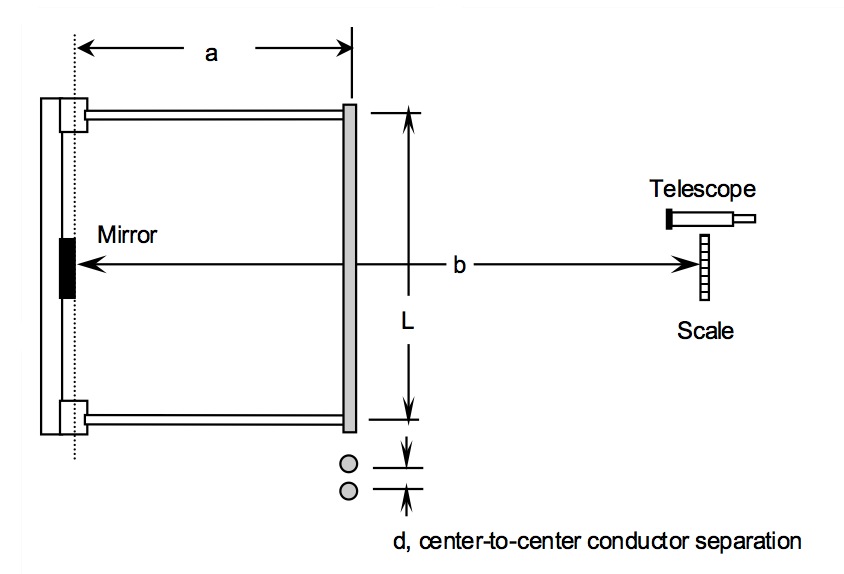

Fig. 88 Schematic and example of setup for testing Ohm’s law.#

Equipment#

Overall setup shown in Fig. 88 right.

Low-voltage DC Power supply (using just ~0 – 6 V)

Three unlabeled ceramic resistors (each < 1 MΩ)

Pasco modular circuit kit

1× Light bulb (DO NOT EXCEED 6 V)

4× Circuit corners

1× Spring clips (to attach individual resistors or series and parallel circuits with alligator clips)

1× Single-pole single-throw (SPST) switch to open and close circuit during reconfiguration and calibration

1× Wireless Current Sensor (Ammeter) – connected to Capstone software

1× Red/black terminals (for connection to DC power supply)

8× U-shaped jumper clips to connect the different modules

1× Voltmeter via Capstone – connected to the jumper clips the on either side of the resistors with alligator clips

Seven wires with alligator clips (multi-colored)

Fluke multimeter with alligator clips

Use as Ohmmeter (Ω) to measure resistors’ and light bulb resistances

Use as DC voltmeter and DC ammeter in series and parallel circuits

Experimental Procedure#

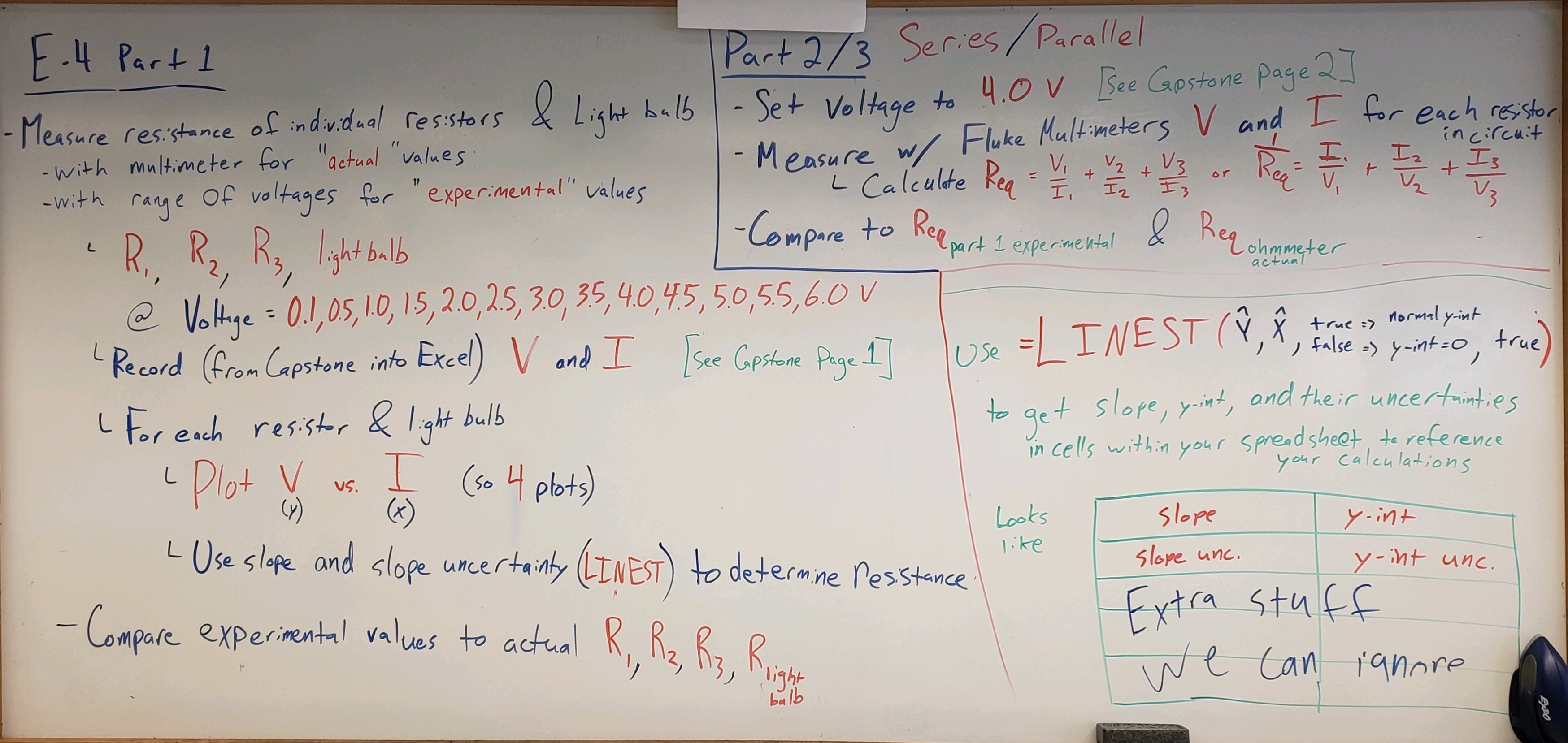

Experiment 1 – Individual Resistors:#

Set up the circuit using the power supply and the resistor \(R_1\) as shown in Fig. 88. It doesn’t matter which resistor you call 1, 2, or 3, just be descriptive and stay consistent. Note: Turn off the power supply and open the SPST switch whenever reconfiguring the circuits or calibrating in Capstone.

With the Fluke ohmmeter, determine actual resistances. You will compare your experimentally determined values to these later on. Attach alligator clips to the ends of the resistors; measure and record the actual resistance of the three resistors, \(R_{1\text{-actual}}\), \(R_{2\text{-actual}}\), \(R_{3\text{-actual}}\) as well as the small light bulb \(R_{\text{bulb-actual}}\).

Create a data table with columns for the measured current, the measured voltage, and the calculated resistance. Include rows for each target voltage for all the \(R_{n=1,2,3}\) and light bulb cases (voltages listed in following steps).

For each voltage setting of the power supply, using the ammeter and voltmeter, measure the current \(I_{n=1}\) through the resistor \(R_{n=1}\) and the voltage \(V_{n=1}\) across \(R_n=1\) where \(n\) is representing each trial (voltage value). The resistance is determined by:

Turn on the power supply and increase the voltage so the voltage \(V_{n=1}\) is about 0.10 V. Measure and record the current \(I_{n=1}\). Then set the voltage \(V_{n=2}\) to about 0.50 V. Measure and record the current \(I_{n=2}\). Proceed in approximately 0.50 V steps for \(V_n\) up to the maximum value for \(V_n\) of 6.00 V. Do not frustrate yourself by trying to set the voltage to exactly 0.50 V steps — just set the voltage to a value near the step and record whatever the voltage and current are! The point here is to have a good sampling across a wide range of voltages.

Repeat the preceding steps for resistors \(R_2\) and \(R_3\).

LIGHT BULB: Replace resistor \(R_1\) with the small light bulb. Repeat the procedure in step 4 increasing the power supply voltage while recording the current. The bulb should be lit at the maximum value of \(V_1 = 6.00\) V. Please don’t over-volt the bulbs, otherwise they’ll burn out sooner.

Plot the voltage (\(y\)) vs. current (\(x\)) for \(R_1\), \(R_2\), \(R_3\), and the light bulb. In your lab submission, consider the four plots including the significance of the shape and the slopes.

Experiment 2 – Resistors in Series#

Replace \(R_1\) with the series connection of \(R_1\), \(R_2\), and \(R_3\) in place of the single resistors (see Fig. 87 top and Fig. 88).

Set the power supply to 4 V (confirm this with the Capstone voltmeter).

Record the current (in series with the circuit) and the voltage (parallel to each resistor) for each of the three resistors with the Fluke multimeter (set to DC amperage and DC voltage, respectively).

Determine the total experimental equivalent resistance:

and compare it with the expected value using (123) and your “actual” resistance values from the Ohmmeter.

Experiment 3 – Resistors in Parallel#

Reconnect the three resistors in a parallel connection (see Fig. 87 bottom).

Set the power supply to 4 V (confirm this with the Capstone voltmeter).

Record the current (in series with the circuit) and the voltage (parallel to each resistor) for each of the three resistors with the Fluke voltmeter (set to DC amperage and DC voltage, respectively).

Determine the total experimental equivalent resistance:

and compare it with the expected value using (123) and your “actual” resistance values from the Ohmmeter.

Post-Lab Submission — Interpretation of Results#

Paragraph of results: Calculate the expected effective resistance using (123) for your series and parallel circuits. Do your measured values agree?

Make sure to submit your finalized data sheet with summarized data and cleaned-up plots (Excel sheet)

Paragraph of your results +/- uncertainties from your data. Make sure to include discussion of the following:

Do your experimental results for the individual resistors and the light bulb agree with your expected values (as measured with the ohmmeter)? Why or why not?

What do the shapes of the plots mean (linear or non-linear relationship?); why, from a physical standpoint, does the light bulb plot look the way it does as compared to the resistors?

Do your experimental results for the equivalent resistances \(R_{\text{eq}}\) ((123)) of both series and parallel circuits agree with their respective expected values based on the resistors’ actual values (from Ohmmeter)?

Physically, why should we expect the resistance of a series circuit to be greater than that of a parallel circuit made of the same resistors?

Paragraph of your errors and estimated measurement uncertainties. Be quantitative. Make sure to include discussion of the following:

Where might systematic (affecting accuracy) and/or random (affecting precision) errors be coming from?

What are your measured uncertainties, and, based on these uncertainties, how do your final results change? I.e. do your different measurement and slope uncertainties make your final results larger or smaller?

If larger or small, are they more or less accurate to expected values?

How could you improve your random errors?

Were your systematic errors significant; how could this be improved if you were to re-run this experiment?

The Whiteboard#

Fig. 89 Overview. LINEST() function.#

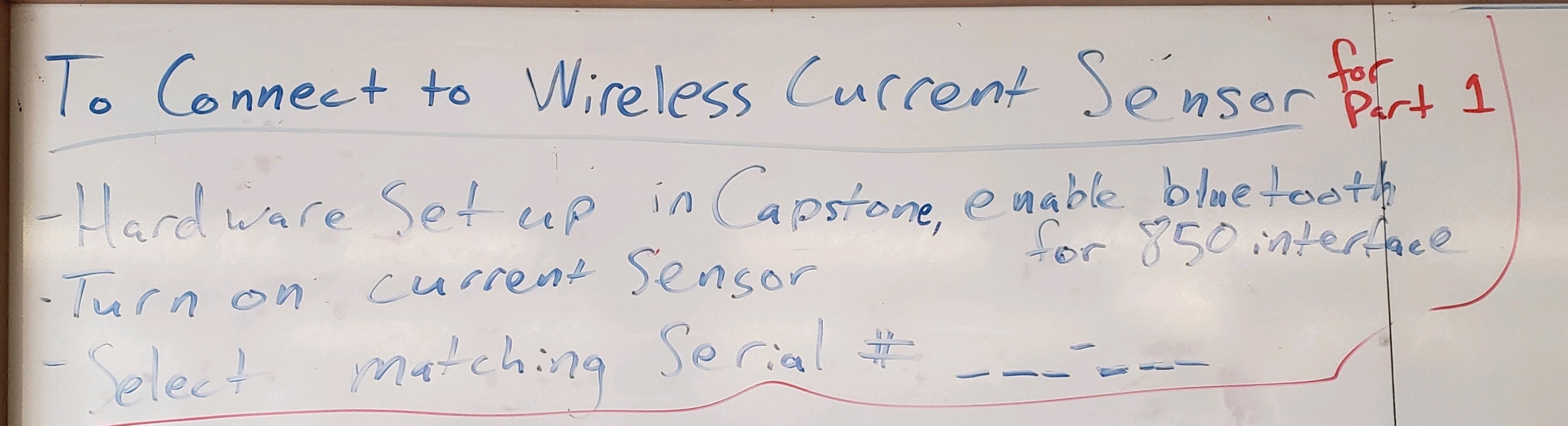

Fig. 90 Sensor setup notes.#

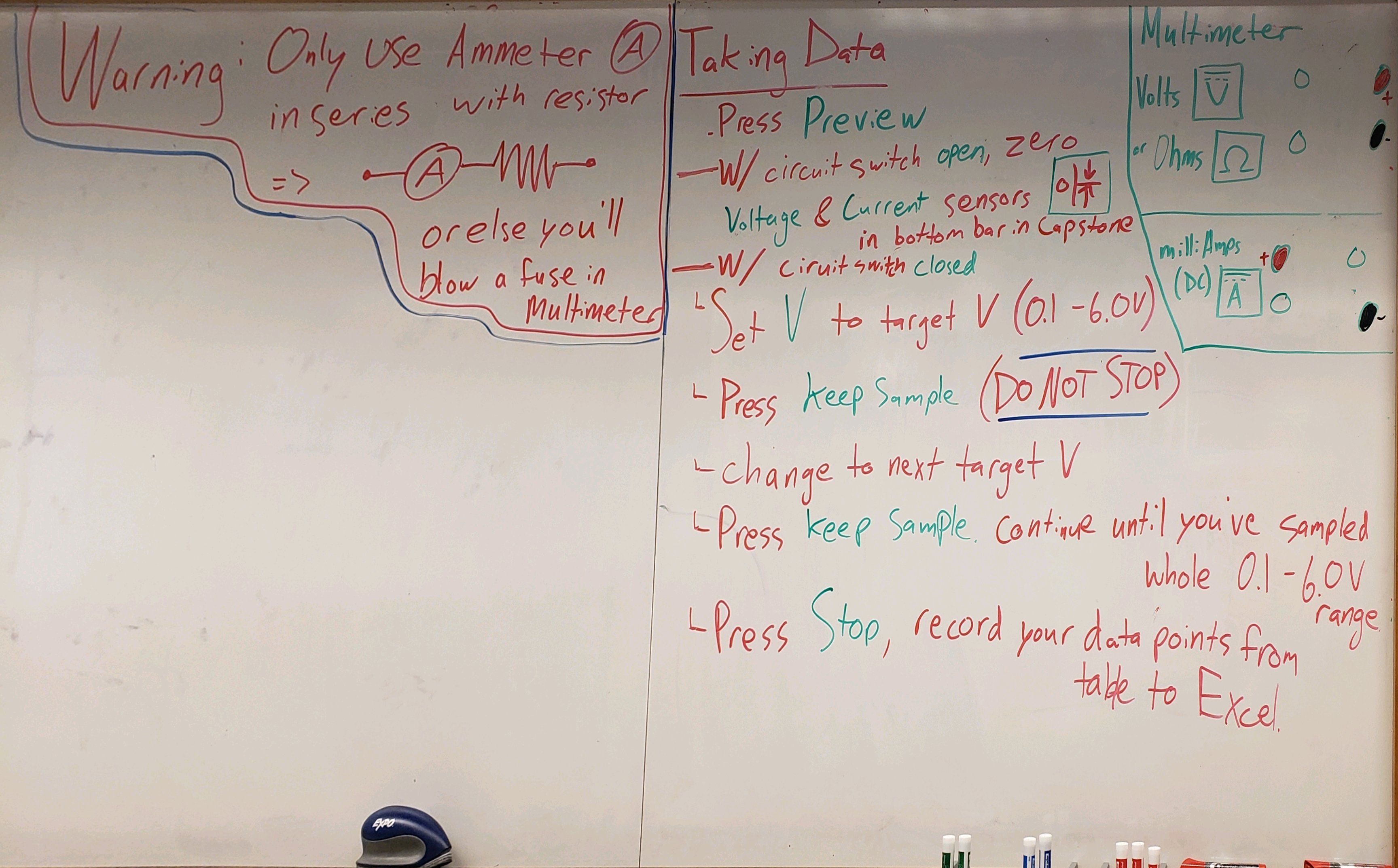

Fig. 91 WARNING — MUST HAVE RESISTOR IN SERIES WITH AMMETER TO AVOID DAMAGE. Data taking notes; multimeter settings.#