Acceleration & Deflection of Electrons#

Background#

Overall goals and overview:#

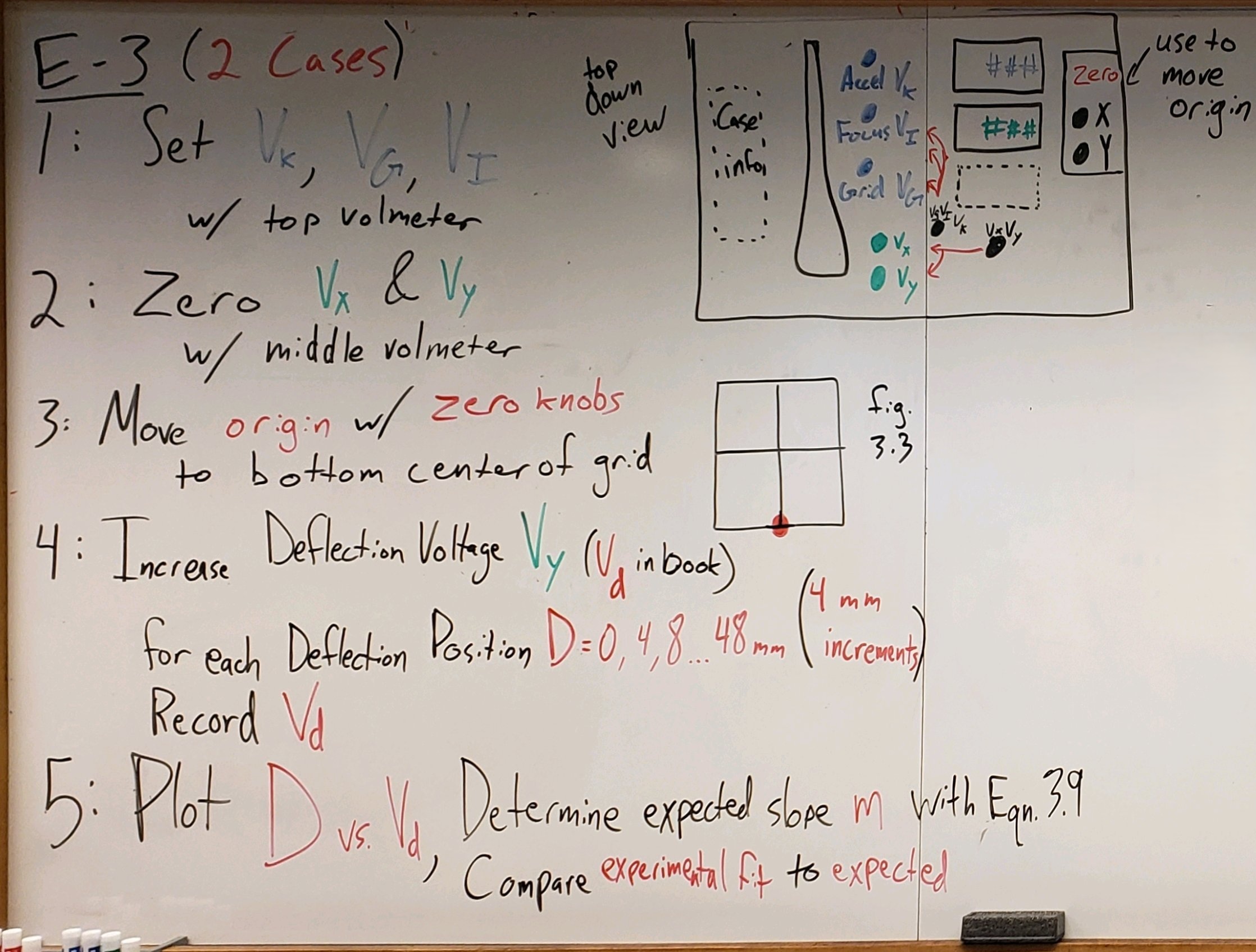

OVERALL GOALS and Overview:

Investigate both the acceleration and deflection of electrons as they pass through uniform electric fields produced by “parallel-plate capacitors” within a CRT.

Analyze the relationship of “electron-deflection distance” vs. “deflection voltage” of a uniform electric field by plotting and comparing to the expected slope based on the internals of your CRT.

In this experiment, you will first set up the grid/focus/acceleration voltages to those listed for each case on the paper inside the apparatus. The X/Y-deflection voltages will be set to zero. The electron beam on the screen can then be moved to the origin with the zeroing knobs. Then the electron deflection in the Y-direction can be measured with the on-screen grid when applying differing amounts of deflection voltage. Then plot \(D\) vs. \(V_d\) and compare to expected values.

The instrument used in this experiment is a cathode ray tube [CRT]. When the filament of this device (also called an electron gun) is heated, electrons (mass = \(9.109 \times 10^{-31}\) kg) are freed and given an acceleration. The acceleration is received when the beam of electrons passes through a region of positive potential with respect to the cathode. Consider the schematic of the tube in Fig. 83.

Fig. 83 Top) Schematic of the Electron Path in the CRT. Bottom) Electron beam path through the CRT.#

The electrons receive an amount of kinetic energy given by

where \(e\) is the charge of the electron and accelerating voltage \(V_{k}\) (often just \(V\), but changed here to \(V_{k}\) for the sake of consistency with the apparatus used today) is the potential difference between the cathode and plate #1 (anode). Thus the velocity in the \(x\)-direction towards the phosphor-coated screen of the CRT, \(v_{x}\) is given by

Then, the accelerated electron beam passes between two parallel plates. If a potential \(V_{d}\) is applied between the plates, the electron beam will be deflected toward the positive plate by a force \(F_E = eE\) where \(E\) is the electric field between the plates and \(e\) is the electric charge. Thus the acceleration in the \(y\)-direction (a.k.a. transverse direction, see Fig. 83) due to the deflection voltage \(V_{d}\) is given by

where \(d\) is the plate separation and \(m\) is the electron mass. Since the electric field between the plates is approximately uniform, the path of the beam will be parabolic in the region between the plates. (Illustrated in Fig. 83, this is a case of an object undergoing uniform acceleration just like an object in projectile motion.) After the beam leaves this space, it will continue in a straight line with a horizontal velocity \(v_{x}\) and a vertical velocity \(v_{y}\) until it strikes the screen at point ‘p.’

The transverse velocity, i.e. in the \(y\) or ‘deflection’ direction we are using today, is given by

where \(t\) is the time during which the particle is accelerated as it passes through the plates of length \(l\). The time t is given by

By combining the above (114), (115), and (116), we obtain the transverse velocity \(v_y\) in terms of measurable quantities, namely

Referring to Fig. 83, the actual on-screen deflection \(D\) from the axis is \(v_{y}\) times the time of flight, \(t^\prime\), over the distance \(L\) from the end of the deflection plates to the screen. Assuming that \(L\gg l\), then the time of flight \(t^\prime = L/v_{x}\). Since distance equals velocity × time, we get

As a result of combining everything we’ve seen so far:

where we see that deflection is directly proportional to deflection voltage \(V_{d}\). Usually, the geometric quantities are held constant but it is interesting to take a look at the effect of these factors on the deflection.

With longer parallel plates there is more time for the electric field to act on the electron beam and cause deflection. Also, the closer the spacing between the deflection plates \(d\), the more intense the field for a given deflection voltage yielding a larger deflection. Finally, the deflection will increase as the accelerating voltage \(V_{k}\) is decreased. This reduces the velocity of the electrons and allows them to spend more time within the deflection field.

The visible spot you see on screen is the result of the energetic electrons releasing their kinetic energy as they impact phosphor atoms. A small portion of that energy is converted to visible light. Most of the energy just heats the screen!

Summing up, the assumptions made in this derivation include:

The geometry of the deflection plates can be considered a ‘parallel-plate’ capacitor configuration. That is, the plates are relatively large and closely spaced. This implies that the electric field is uniform, vertical, and completely contained between the deflection plates.

The distance to the screen is large compared to the horizontal size of the deflection plates (\(L\gg l\) in Fig. 83), so the electron path may be considered to be a straight line from the center of the deflection plate configuration to screen.

The electron beam’s enters with an initial direction that is parallel to the deflection plates.

Equipment#

Complete Properties of Electrons Apparatus

List of experimental cases with their voltages

Cathode Ray Tube (CRT)

5 mm grid pattern on end of CRT

Knobs for controlling X & Y zeroing, X & Y deflection voltages, and accelerating, focus, grid voltages

Voltmeters for the different sections on the apparatus (See the black-outlined sections on the apparatus for which voltmeters go for which knobs)

Experimental Procedure#

Fig. 84 Controls and parameters for the CRT.#

All knobs, switched, displays are numbered and will appear as (#) in the following steps which correspond to those shown in Fig. 84.

Turn on the main power switch (10), and wait until the cathode warms up and a bright spot appears on the screen. If it doesn’t appear after ~30 s, an instructor can be of assistance; it’s likely a deflection or zeroing knob pushed the beam off-screen.

FOR CASE 1 as listed on apparatus. Set the CRT voltage selector switch (3) to read the grid voltage \(V_{G}\). Adjust the grid voltage to the given value using the grid potentiometer (17) whose voltage appears on the top voltmeter display (24).

Now set the CRT voltage selector (3) to read the focus voltage \(V_{I}\). Adjust the focus voltage to the given value using the focus potentiometer (20) whose voltage also appears on the top voltmeter display (24).

Next, set the CRT voltage selector (3) to read the acceleration or cathode voltage \(V_{K}\). Set the accel. voltage to the given values using the accel. potentiometer (21) whose voltage also appears on the top voltmeter display (24). (\(V_{K, case 1} = 950\) V, \(V_{K, case 2} = 1100\) V)

Set electrostatic deflection selector switch (8) to X-deflection \(V_{x}\), and set the X-deflection voltage potentiometers (13) to zero (0.0 V) which appears on the middle voltmeter display (23).

Set electrostatic deflection selector switch (8) to Y-deflection \(V_{y}\), and set the Y-deflection voltage potentiometers (12) to zero (0.0 V), again appearing on the middle voltmeter display (23).

Then, use the ZERO X and Y potentiometers (1) to move the bright electron-beam spot to the bottom center of the screen grid (see Fig. 85). These knobs do not change the Electrostatic Voltages in (23); if the voltages do change, check you are in fact using the ZERO knobs (1), not (12) or (13). Make sure to view the CRT head-on so as to account for possible misalignment from the effects of parallax (since the grid is horizontally displaced from the glass of the CRT).

Fig. 85 Example of CRT grid and 4 mm spacings.#

Ensure the deflection voltage switch (8) is set to read the deflection voltage \(V_{y}\). Since we are only deflecting electrons in the \(y\)-direction, we will refer to the deflection voltage as \(V_{d}\) (i.e. \(V_{d} = V_{y}\)).

Create a common data table and record the grid voltage and the focus voltage. Record the following CRT data:

\(d\) = spacing between plates listed on the apparatus

\(l\) = length of horizontal deflection plates (parallel plates)

\(L\) = distance from plates to screen of tube

Create a data table with columns for the deflection voltage \(V_d\) and the deflection position \(D\) (e.g. 0, 4, 8, … 48 mm). \(D\) is based on the CRT grid and not to be calculated. At the start of each case, list the acceleration voltage, the grid voltage, and the focus voltage. Throughout the case, estimate and note your uncertainty in deflection position \(\delta D\).

Note the initial deflection voltage \(V_{d}\) at \(D=0\) mm, then slowly increase the y-deflection voltage \(V_{d}\) using the \(y\)-deflection potentiometer (12). Move the bright spot 4 mm and record the deflection voltage \(V_{d}\). Continue this process every 4 mm up to 48 mm for a total of 13 data points. Double check: The acceleration voltage \(V_{k}\) and the horizontal deflection voltage \(V_{x}\) must be constant during this procedure.

FOR CASE 2, repeat steps 3 to 12 above using Case 2 data listed on the apparatus including an acceleration voltage of 1100 V.

For each case, plot your values of deflection distance \(D\) vs. deflection voltage \(V_{d}\). Reminder, \(D\) is not calculated, but rather just your 4 mm increments. Draw a best fit line through the data points and determine the slope, \(m_\text{experimental}\) of the line and the slope’s uncertainty \(\delta m_\text{experimental}\) (available either on the trend line equation or with the LINEST() function).

Compare your data fit (slope) with the expected slope as predicted by the equation for \(D\) vs. \(V_{d}\), namely

where \(m\) is the slope of the line.

For each case individually a. Use all 13 of your experimental deflection positions \(D\) and their deflection voltages \(V_d\) as well as the slope \(m\) of your best-fit line found in Step 14 to calculate the square root of the mean of the square difference between your data and the best fit line (i.e. you’re calculating the root mean square or RMS of the difference between what you claim the deflection position \(D\) is and what the best fit line of your data says the deflection position should be). For each of your 13 data points, you will have a squared difference of \((D - m V_d)^2\).

b. From those 13 values, you can take the mean, then the square root of that mean value for a resulting single value:

(121)#\[\sqrt{\text{mean}(\text{all 13 squared differences})} = \sqrt{\text{mean}((D - m V_d)^2)}\]where \(D\) are your claimed 4 mm incremented deflection positions, \(m\) is your experimental slope, and \(V_d\) are your experimentally determined deflection voltages.

c. Compare this RMS value to your estimate of how well you can read displacements on the screen (i.e. comparing to position uncertainties \(\delta D\)).

Post-Lab Submission — Interpretation of Results#

Make sure to submit your finalized data sheet with summarized data and cleaned-up plots (Excel sheet)

Paragraph of your results +/- uncertainties from your data. Make sure to include discussion of the following:

Do your experimental results (slopes) agree with the expected slopes as predicted by (120)?

Physically, what do your experimental slopes represent?

If you were to increase the accelerating voltage \(V_{k}\), how do you expect the beam to be deflected? I.e. what does the accelerating voltage physically do to the electrons, and how do changes in the \(V_{k}\) affect the electrons’ path? Discuss using physical concepts regarding the electron path.

Explain physically how the electron mass cancels and as a result does not appear in (119).

Paragraph of your errors and estimated measurement uncertainties. Be quantitative. Make sure to include discussion of the following:

How does the uncertainty (RMS) of your plotted data compare to your estimated position uncertainty on the screen? Does the full data better represent the physical relationship we’re studying in this lab than your estimation of individual positions (be quantitative)? This is based on your values from Step 16.

Where might systematic (affecting accuracy) and/or random (affecting precision) errors be coming from?

What are your measured uncertainties, and, based on these uncertainties, how do your final results change? I.e. do your different measurement and slope uncertainties make your final results larger or smaller?

If larger or small, are they more or less accurate to expected values?

How could you improve your random errors?

Were your systematic errors significant; how could this be improved if you were to re-run this experiment?

Reflect on this week’s lab; what did you learn?

The Whiteboard#

Fig. 86 Overview.#