Measurement of Helmholtz Magnetic Field & Electrons’ e/m Ratio#

Background — Part I — e/m Ratio of the Electron#

Overall goals and overview#

Experimentally determine the charge to mass (e/m) ratio for the electron with the use of an electron beam inside a vacuum bulb inside Helmholtz coils

Understand the relationship between magnetic force and electron deflection. Consider: if magnetic force increases, what happens to the electrons’ path and why physically is that happening?

In the first experiment, you will conduct nine total trials where you will change both the acceleration voltage and coil current to measure the shape of the electrons’ path. The path will be measured at the furthest right and left extremes of the electron beam.

In the second experiment, you will quantitatively measure the magnetic field strength in the region of the electron beam and qualitatively consider the B-field within Helmholtz coils (without a vacuum bulb). DO NOT REMOVE THE BULBS! THIS IS A DIFFERENT SETUP BY THE BACK OF THE ROOM.

One of the most important pieces of information concerning the nature of electrons can be obtained by observing their motion in a magnetic field. It is a relatively easy task to determine the charge to mass ratio of the electron with the apparatus provided.

An electron, emitted from the cathode with speed \(v\), enters the magnetic field set up by the Helmholtz coils (see experimental setup and B-field shape in Figure 107). According to the right hand rule, which is described in your text, the electron will experience a centripetal force causing it to move in a circular path. Therefore, setting the magnetic force equal to the mass times centripetal acceleration (Newton’s Second Law) yields:

Rewriting this expression, we obtain:

where \(B\) is the magnetic field, in this case given by \(7.4 \times 10^{-4}\) times the current, \(I\), in amperes, that is:

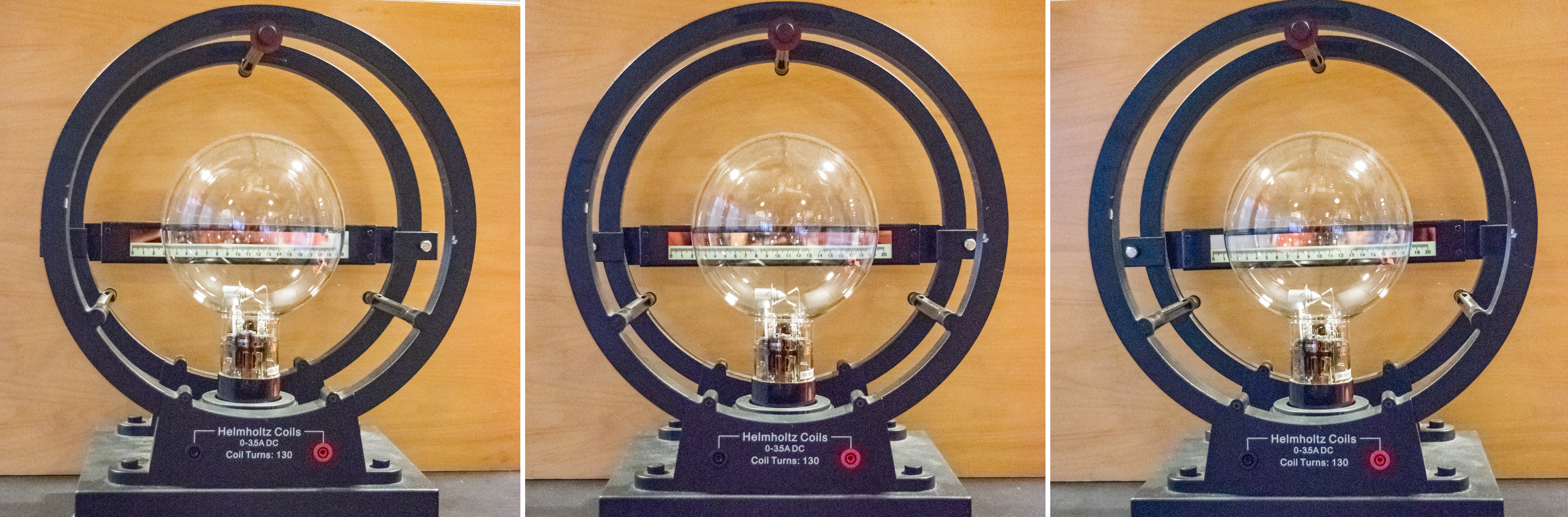

The radius \(r\) of the circular path is measured using a scale with a mirror above it to eliminate parallax (example in Figure 106).

Fig. 106 Effects of parallax from head-on view: slightly to the left, center, and slightly to the right. The ruler at the back (and the rear coil) is clearly out of line with the line of sight depending on where you are looking from. View the electron beam such that you overlap its reflection in the mirror to account for the parallax.#

One method of obtaining a value for \(v\) makes use of the fact that a charged particle gains an energy \(e\,V\) when it falls through a voltage \(V\). Therefore, if we knew the voltage through which the electron was originally accelerated, we could write \(e\,V =\frac{1}{2}m v^{2}\) or:

Substituting for v in the expression for e/m, we obtain:

Notice that we need know only the voltage through which the electron was accelerated, in addition to the value of B and r, in order to evaluate the ratio \(e/m\) for the electron. The accepted value for e/m for the electron is \(1.759\times 10^{11}\) C/kg.

The path of the electrons is made visible by the bombardment of gas atoms in the tube. The impact of the electrons on the atoms increases the energy of electrons in those atoms. These atoms spontaneously fall back to lower energy states by emitting the blue light that you see as the circular path of the electrons. Since the electrons will lose some energy when they bombard gas atoms, the brightest part of the path is not where the electrons with their ‘full’ energy are. The electrons that have energies closest to the energy we assume for them, namely \(e V\), are at or near the outer edge. Thus the radius of the circular path which corresponds to the assumed electron velocity are at or near the outer edge. As the electrons bombard the gas atoms, they lose energy. As a result, they ‘drop’ into a smaller orbit. You can observe this process by observing the spreading of the illuminated path as the electrons move around their orbit. For this reason, it is important to measure the diameter of the orbit from the outer edge.

Fig. 107 Left) Helmholtz coils with vacuum bulb in place (first experiment). Center) Helmholtz coils without bulb (similar to setup you’ll have in second experiment). Bottom) Mirror and ruler, movable to line up with the greatest extents of the electron beam. Right) Magnetic field lines of a pair of Helmholtz coils.#

Equipment#

Experiment I

Helmholtz coils with cover and bulb

Wire wound in two large coils of 130 turns each, spaced one radius apart for consistent B-field

Cathode ray bulb at low-pressure/near-vacuum (source of electron beam)

Repositionable ruler with a mirror to view electron beam position

Low voltage DC power supply, 0 – 24 V which runs current through the wire coils to generate a magnetic field

High voltage DC power supply

0 – 500 V, accelerates the electrons straight ahead from the cathode

~6 V AC power to heat up the cathode and generate electrons

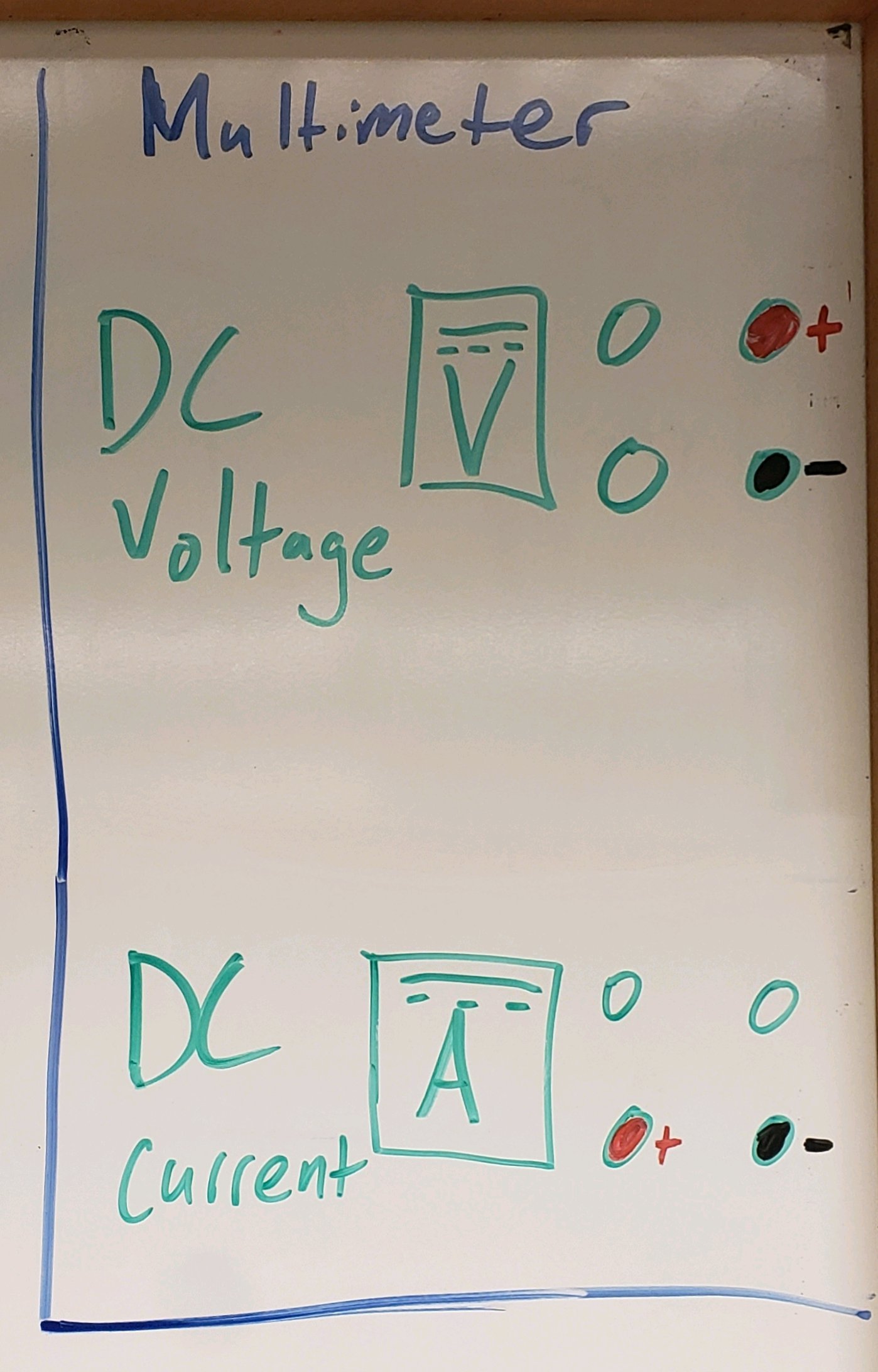

x2 Fluke multimeters –

One in series, set to read DC current of the coils

One in parallel to read DC voltage of accelerating voltage of the electrons

Flashlights

3x 3’ banana-plug cables

5x 2’ banana-plug cables

3x 1’ banana-plug cables

Experiment II, discussed further after experiment I.

Helmholtz coils, empty (DIFFERENT APPARATUS, DO NOT REMOVE THE BULBS FROM THE FIRST PART!)

Wire wound in two large coils of 130 turns each, spaced one radius apart for consistent B-field

NO cathode ray vacuum bulb (do not remove the bulbs)

Fluke multimeter in series, set to read DC current of the coils

PASPORT 2-Axis Magnetic Field Sensor (axial measures positive B-field into the end of the probe; perpendicular measures positive B-field upwards through the probe)

\pagebreak

Experimental Procedure — Part I — e/m Ratio Measurement#

In doing the experiment, caution must be exercised in using the HIGH VOLTAGE DC power supply. Before beginning the experiment, ask the instructor to indicate the proper procedure for operating the various power supplies and meters required.

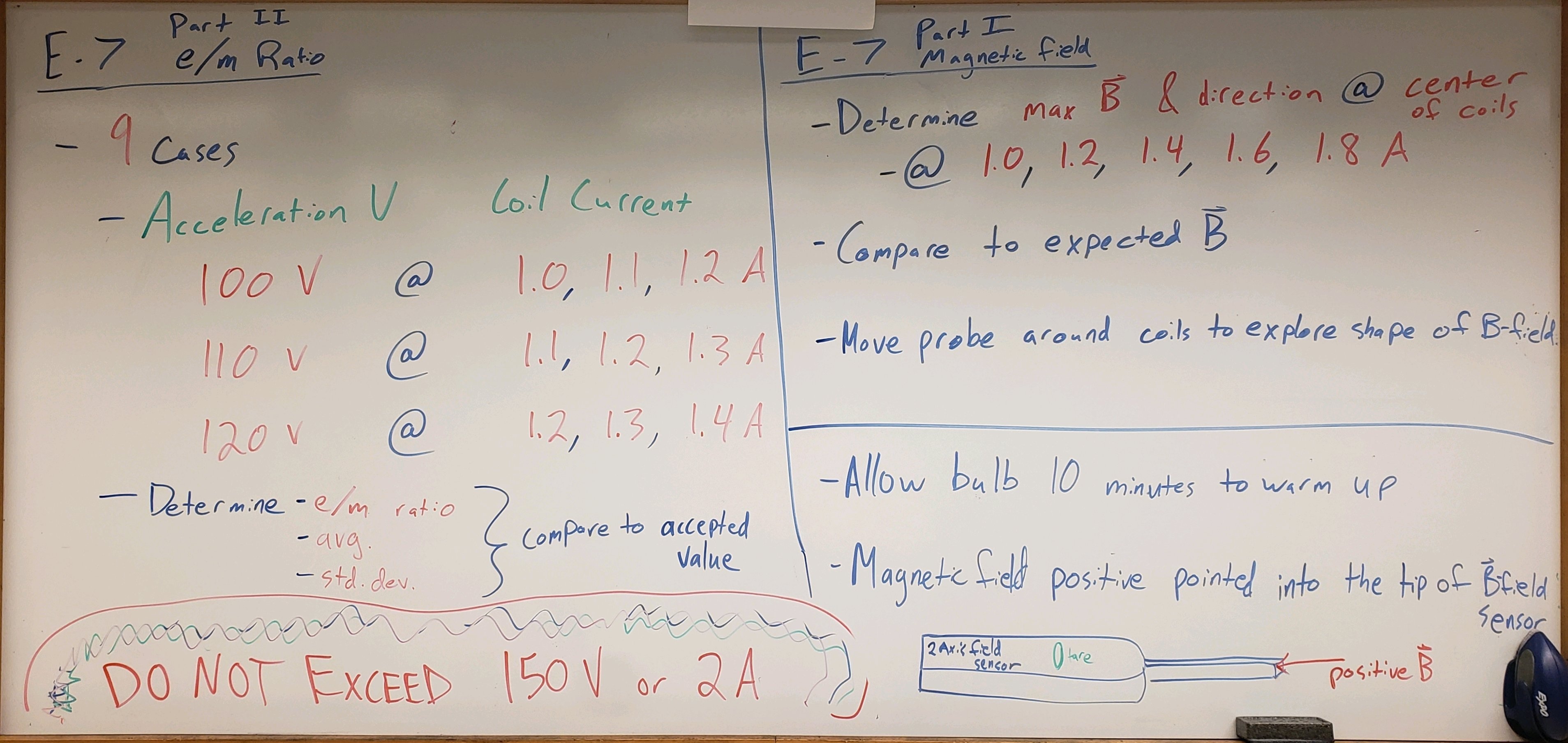

Create a data table with columns for the accelerating voltage, the current in the coil, the magnetic field, the left and right edges, the diameter, and the radius in [m]. Include a column for the ratio \(e/m\) calculated in each row from your measurements. The nine trial voltage, current combinations are:

\(V=100\) V, \(I=1.0, 1.1, 1.2\) A

\(V=110\) V, \(I=1.1, 1.2, 1.3\) A

\(V=120\) V, \(I=1.2, 1.3, 1.4\) A

Adjust the accelerating voltage and current values indicated in the data table for Trial #1. DO NOT EXCEED 150 V OR 2.0 A AT ANY TIME!

With the electrons traveling in a circular path, the radius of the path will be determined by measuring the diameter and dividing by two. Therefore read the scale on both the left and right edges of the circular path. The scale and mirror at the rear of the tube is adjustable. Position the top of the scale horizontally at the center of the circular beam path. YOU MUST MOVE THE RULER UP OR DOWN TO BISECT THE CIRCULAR BEAM TO COVER WIDEST EXTENT OF THE CIRCLE.

The readings must be taken at the beam’s widest edges. When determining the scale reading, close one eye and move your viewpoint so the electron path and its reflection in the mirror can be made coincident; this is correcting for parallax arising from the electron beam and ruler existing in different planes (similar to the grid and screen of the CRT in the Acceleration of Electrons lab). Align one side of the beam with its image in the mirror and read and record the position on the scale of the farthest part of the beam from the center. Then move your viewpoint to align the other side of the beam its image in the mirror and again read the scale.

Determine radius: First obtain the diameter as the difference of the two positions. Read and record the scale reading to the nearest millimeter. Try to read and record the outside edges of the path for the energy-related reasons discussed previously. Subtract the reading on the left edge from the reading on the right edge to calculate the diameter. Divide the diameter by two to find the radius and record this value in the data table.

Reset the voltage and current to the values indicated for each of the subsequent trials and record the corresponding radii.

If any trials are clearly erroneous, retake the data.

Calculate the average and standard deviation of your \(e/m\) values and compare them to the accepted value. Does your average value agree with the accepted value within your standard deviation range?

Background — Part II — Magnetic Field Measurement#

STOP!!! DO NOT REMOVE THE BULBS! THIS IS A DIFFERENT SETUP BY THE BACK OF THE ROOM. You will use the Helmholtz coils that already are without the vacuum bulb.

The magnetic field produced near the axis of a pair of Helmholtz coils is given by the equation:

where:

\(a = 0.15\) m (radius of the Helmholtz coils)

\(N = 130\) (the number of turns on each Helmholtz coil)

\(\mu_0 = 4\pi\times 10^{-7}\) N/A² (the permeability of free space)

\(I\) = the current through the Helmholtz coils

and \(B\) has units of Tesla.

Experimental Procedure — Part II — Magnetic Field Measurement#

While this set of Helmholtz coils is different to the one you used earlier, they are approximately the same size with the same number of wire turns and should produce a magnetic field comparable to the one the electrons were accelerating through earlier.

In CAPSTONE, click “Record” and the magnetic field strength in the axial direction will be displayed in Tesla (T). Before taking measurements, turn off the low-voltage power supply that is providing the current through the coils — we want to account for all magnetic fields not generated by your Helmholtz coils. Be sure to press the green Tare button on the sensor to zero it while holding the sensor inside the coils. Using both the voltage and current controls on the power supply, gradually increase the current to 1.00 A through the Helmholtz coils. Please do not exceed 2 A at any time (we don’t want them burning out or breaking). Using the magnetic field sensor, determine the strength and direction of the magnetic field near the center of the coils. Repeat for currents of 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 A.

Using the magnetic field sensor, explore the region within the coils and describe the region of consistent or inconsistent B-field.

Compare your values for magnetic field strength near the axis within the coils to the expected values from (145).

You can also explore around the coils and find the shape of the magnetic field changes direction outside of the coils as in Figure 107 right.

\pagebreak

Post-Lab Submission — Interpretation of Results#

Make sure to submit your finalized data sheet with summarized data and cleaned-up plots (Excel sheet)

Paragraph of your results ± uncertainties from your data. Make sure to include discussion of the following:

For the Helmholtz coils with bulb, do your experimental results agree with the accepted values of \(e/m\)?

Why, physically, do the electrons travel in a circle, rather than just continuing in a straight line?

For the empty Helmholtz coils (no bulb), where does the magnetic field peak and where does it go to zero; physically, why does that happen?

Does the measured B-field in the center of the coils agree with the expected field strength from (145)?

Was the B-field consistent in the center where the \(e/m\) bulb would sit? I.e by how much does the field strength vary when moving from the center of the coils the widest extent of the electron beam from the first experiment?

If we used this new measured value for B-field back in the first experiment (from (144)), how do your results for \(e/m\) change (larger/smaller, by how much)?

Paragraph of your errors and estimated measurement uncertainties. Be quantitative. Make sure to include discussion of the following:

Where might systematic (affecting accuracy) and/or random (affecting precision) errors be coming from?

What are your measured uncertainties, and, based on these uncertainties, how do your final results change? I.e. do your different measurement and slope uncertainties make your final results larger or smaller?

Change different variables by your best estimation of measurement uncertainties in your Excel sheet; what variables affect the accuracy of your final results the most?

If larger or small, are they more or less accurate to expected values?

How could you improve your random errors?

Were your systematic errors significant; how could this be improved if you were to re-run this experiment?

Reflect on this week’s lab; what did you learn?

The Whiteboard#

Fig. 108 Overview.#

Fig. 109 Multimeter settings.#