1172L-ONLY | Faraday’s Law of Induction#

Background#

Overall goals and overview#

Explore magnetic flux, Faraday’s Law, Lenz’s Law, and mechanical energy dissipation through the aforementioned concepts.

Understand the relationship between magnetic flux and electro-motive force (EMF; effectively an induced voltage due to changes in magnetic field)

In this experiment, you will:

First determine the maximum magnetic field strength of the horseshoe magnet through where the wand’s coil passes.

Second determine average voltage and integrated voltage (area under curve) of the wand passing through the magnetic field and compare to expected values of the induced voltage (EMF).

Third determine the amount of energy lost due to friction (with angles of the rotary sensor for change in gravitational potential energy), energy lost due to the resistor (area under power curve), and total energy lost (again with angles).

Magnetic Flux#

The magnetic field in a volume of space can be described by vectors, which give the strength of the field (its magnitude) and the field’s direction at each point of the volume. A closed loop (closed, so that the area of the loop is defined) will then have field vectors “punch through” the area bounded by the loop. One can think of this as the field “flowing” through the area defined by the loop (very similar to water flowing through a cross sectional area of a pipe). This flux can be defined by:

Note that, the second equation holds only if \(B\) is constant over the area defined by the loop. The flux will be zero if the magnetic field is parallel to the area of the loop and maximum if the field is perpendicular to the area of the loop.

Faraday’s Law#

If a loop of wire (for example a coil) is moving in a magnetic field or if the magnetic field over the area of the loop changes (either direction or magnitude) then an electro-magnetic force (a voltage) might be induced in the loop due to the fact that the magnetic flux through the loop changes. Faraday’s Law states that the induced electro-motive force [EMF] or voltage in the loop is directly proportional to the rate of change of the flux through the loop. In this experiment, the magnet and coil are arranged so that the magnetic field is perpendicular to the coil loops and:

Here \(N\) is the number of windings in the coil and the negative sign in front of the expression indicates that the EMF is induced in such a way that it opposes the change in flux through the loop (this is commonly known as Lenz’s Law).

In this lab the area of the coil is constant, but the field through the area defined by the coil will change. Therefore Faraday’s Law here can be written as:

or, if we average over a time \(\Delta t\):

Integrating (147) gives:

If the area is integrated from the beginning of the peak to the point where the voltage is zero and the coil is at the maximum field, then \(\Delta B\) will equal the maximum field. Capstone has an area function that can be used to measure the integral of the voltage.

If the coil is in a closed circuit with total resistance \(R\) then a current will flow through the coil according to Ohm’s Law:

The circuit will dissipate energy at a rate of:

Since power is work per time, the energy that is lost in the circuit can be found by calculating the area under the power vs. time graph (i.e. the integral of the Power \(P\) over time \(t\)):

Energy in a pendulum#

The center of mass of a pendulum starting at an initial height \(h_{i}\), then swinging through its lowest point and finally rising to a height \(h_{f}\), will experience a change in potential energy of:

If no energy was dissipated, then the change in potential energy would be zero (no potential energy would be lost in this case). If the final height were less, as indicated in Figure 110, then the change in energy would give the energy lost during the motion:

Finally the initial and final heights can be related to the angles \(\theta_i\) and \(\theta_f\) the pendulum makes with the vertical direction at these location (see Figure 110):

In this equation \(L\) indicates the distance from the center of mass to the pivot of the pendulum.

Fig. 110 This picture shows the coil wand swinging from an initial angle \(\theta_{i}\) to a final angle \(\theta_{f}\). The final angle is less because of energy lost in the process, which reduces the potential energy by an amount \(E_{Lost}\) (see (156)).#

Fig. 111 Left) Coil wand with resistor and an example of the center of mass line and mass noted on the wand itself. Center) Resistor and circuit diagram of the wand; resistor plugs in and completes the circuit allowing energy to be dissipated. Right) Internals of the wand; wires lead from the ports to the coil at the bottom of the wand. The area of the loop refers to the area inside the white loop of wire at the bottom.#

Equipment#

Variable Gap Horseshoe Magnet

Induction Wand as shown in Figure 111. The number of turns of the coil is \(N=200\) and the area of the coil is \(A = \pi r^2 = \pi (0.013\,\text{m})^2\).; mass and center of mass are noted on the white label.

\(\sim 4.7\,\Omega\) resistor (you will measure your resistor directly to confirm later on). It can be inserted into the wand to complete the circuit in the wand in order to measure the energy dissipated in the resistive load by the induced current.

Stand, rods, and clamps

Voltage Sensor to Capstone; records the voltage induced in the coil. The plugs of this sensor are connected to the jacks at the end of the coil wand. The voltage sensor is plugged into an analog input with a sample rate set to \(1000\,\text{Hz}\).

PASPORT 2-Axis Magnetic Field Sensor (axial measures positive B-field into the end of the probe; perpendicular measures positive B-field upwards through the probe) for measuring strength of horseshoe magnet.

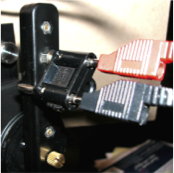

Rotary Motion Sensor (RMS) connected to Capstone. Detects and measures angular displacement, angular velocity, and angular acceleration. A 3-step pulley is affixed to its axle (see Figure 112). The coil wand is mounted onto the 3-step pulley so that the rotational motion of the wand (and therefore the coil) can be measured. The RMS is set to a nominal sample rate of \(500\,\text{Hz}\).

Experimental Procedure#

Fig. 112 This picture shows the coil wand mounted on the RMS as well as the horseshoe magnet. The cables connecting to the voltage sensor are plugged into the two jacks at the top of the wand. The magnetic field sensor can be seen in the foreground.#

The experiment should be already set up for you as shown in Figure 112.

Magnetic Field measurements

Set gap between the plates on the magnet to \(1.5\,\text{cm}\) (Case 2 will be \(3.0\,\text{cm}\)).

Starting in the first tab in the Capstone file, click Record and use the magnetic field sensor to measure the magnetic field strength between the poles of the magnet. First press the Tare button on the 2 Axis Magnetic Field Sensor with it held far from the magnets. Hold the field sensor sideways (same position as in Figure 112) and insert the tip into the gap between the poles of the magnet. When the measured field is positive the label of the magnetic field sensor points towards the South pole of the magnet. The magnetic field direction as measured (positive or negative) is as shown in the diagram on the sensor. The field lines coming out of the side of the sensor with the diagram and tare button on it indicate the magnetic field strength as positive, pointing North to South when external to the magnet.

Hold the Induction Wand pendulum up out of the way. Insert the Magnetic Field Sensor probe between the magnetic pole plates. If the pole plate on the same side as the label on the magnetic field sensor is a south, the Magnetic Field Sensor signal is positive.

Click RECORD. Use the Magnetic Field Sensor to determine which pole plate is north and put a label on it. You will need that for the Lenz’s law part of the experiment. If a compass is available, check to make sure you have labeled your magnet correctly.

Use the Magnetic Field Sensor to probe the field between the plates. Record the maximum field at the center of the plates. Next, determine the distance from the horseshoe magnet where the field drops to less than \(0.001\,\text{T}\). You will start the coil wand swinging this far from the magnet so that it begins its swing in approximately zero field. Enter your values in the Magnetic Field Data table.

Click STOP. Click Delete Last Run at the bottom of the screen.

Induced Voltage (EMF)

In this section you will compare the calculated and experimental \(\mathcal{E}\) (EMF or voltage) induced in the wand’s coil.

The coil should be able to move freely through the gap between the magnet poles, with the poles as close together as possible (about \(1.5\,\text{cm}\) between the plates) without restricting the motion of the coil. The center of the coil should be moving right through the middle of the poles. The long axis of the plates is horizontal so the pendulum swings through a more uniform magnetic field.

Switch the Capstone file to the second tab, with Voltage vs. time and angle vs. time plots.

Ensure the Voltage Sensor banana plugs are plugged into the banana jacks on the end of the coil wand. Drape the Voltage Sensor wires over the rods so the wires will not exert a torque on the coil as it swings.

Let the pendulum hang at rest. Press RECORD, and ZERO the voltage sensor by looking in the bottom recording bar, with the voltage sensor selected, click the zero button (zero with two yellow arrows pointing towards each other).

You can now pull the pendulum back. Let the pendulum swing freely and ensure the pendulum can swing 10 oscillations over about 10 seconds. If it’s longer, you may have extra friction from the wand hitting/scraping against the magnet or wires. No data is needed for this step, just double check your setup. Once you’re sure the pendulum can freely swing, move on to the next step.

WITH THE PENDULUM AT REST, click RECORD and pull the coil wand out a bit further than the zero-B-field position you measured in step 2 above (\(\sim 25°\)). Release the wand and let it swing through the magnet out and back once. Then click STOP. The graph should show at least two up pulses and two down pulses.

Press the “Stop” button on Capstone.

Enlarge the portion of the voltage vs. time graph where the coil passed through the magnet.

Enable and use the Multi-coordinates tool (four black arrows pointing to each other in the top toolbar of the plots) to determine the difference in time from the beginning to the end of the first peak.

Find the average voltage by highlighting the first peak from when voltage lifts off from zero and returns to zero. \item Find the experimental area under the curve of the voltage versus time graph for the first peak using the area tool. You will have to CHANGE the tool properties number format to show sufficient significant digits. \item Calculate the expected value of the average induced voltage using (149). Calculate the expected area of the induced voltage using (150). Use \(N = 200\) for the number of turns of the coil and \(A = \pi r^2 = \pi (0.013\,\text{m})^2\) for its area. \item\label{E8Item:analysis} Compare your experimental and expected values. \item\label{E8:PascoA11} Increase the magnet gap to \(3.0\,\centi\meter\) and repeat the steps~\ref{E8:PascoA3} to~\ref{E8Item:analysis}, except start the pendulum from the same position you used before. \end{enumerate}

\item Lenz’s Law \begin{enumerate} \item Think about this section as you will need to cover it in your post-lab submission. \item Look at the circuit diagram showing the coil orientation printed on the Induction Wand. Note that we have connected the red plug from the Voltage Sensor to the upper port and the black plug to the lower port. If coil current flows in the direction shown by the arrows (clockwise), then the upper port becomes positive due to excess positive charge there, and the lower port becomes negative due to decrease in positive charge. Since the red lead from the Voltage Sensor is attached to the upper port, the Voltage Sensor would read a positive voltage. Caution: although current flow in an external circuit is from positive to negative, current flow inside a battery or power supply must be from negative to positive. \item Lenz’s Law states that the current induced in a coil by a changing magnetic field through the coil will flow in a direction to oppose the change which produced it. In particular, the field produced by the induced current will be in a direction to try and prevent the field through the coil from changing. \item The magnetic field points from the north pole to the south pole. As the coil enters the magnet, the magnetic flux increases in that direction. Lenz’s Law says that the induced voltage opposes the change in flux. For the first peak, since the coil is entering the field, what does Lenz’s law say the induced voltage of the first peak compared to the second peak; should they both be positive or negative, or should one be positive and one be negative? Does it matter which direction the coil is moving or which direction the magnetic field is pointing? \end{enumerate}

Fig. 113 This picture shows the resistive load attached to the coil wand. The cables leading to the voltage sensor are plugged into the resistor. In order to disconnect the resistor without changing the mass-distribution of the coil wand only one of the resistors plugs is connected to the jacks of the wand.#

Energy

Open the Capstone file.

In Capstone, on the left side, click on the calculator. With the coil out of the magnetic field, use an ohmmeter to measure the resistance of the coil in the induction wand. Why must the coil be out of the field of the horseshoe magnet when measuring resistance? Verify the resistance of the \(4.7\,\Omega\) resistor. Enter the correct resistance values in the calculator and click accept. Finally click the calculator to close it. Before you start each new trial, click the calculator to make sure the resistor values are correct and have not reverted to the default values.

Plug one side of the \(4.7\,\Omega\) resistor into the coil wand.

Remove the magnet pole plates. Move the magnets as close to each other as possible, making sure that you leave enough space for the coil to move through the gap. Connect the RMS and the voltage sensor.

Measure the distance of the center of mass of the wand (marked on the wand) from the pivot (the screw). Note the result in the data table.

Note the mass of the wand (noted on the wand) in your data table.

First determine the amount of energy lost to friction by letting the pendulum swing through the magnet with the resistor disconnected. This is done by having the resistor plugged into the wand with only one of his plugs connected (see Figure 113). This makes sure that no current flows through the wand (and the resistor) while leaving the center of mass of the wand unchanged.

Press the “Record” button on Capstone with the coil at rest between the magnet poles. The rotary sensor zeros itself out whenever you start recording, we want to make sure \(0°\) is when the wand is at rest.

Rotate the wand to an initial angle of \(25°\) and let it go.

Press the “Stop” button after the wand has reached the other side.

Use the “Magnifier” tool to enlarge the portion of the angle vs. time graph where the coil passed through the magnet. Select the peak and get the maximum and minimum angle of the motion to find the initial angle (\(\theta_{i}\)) and the angle to which the pendulum rises after it has passed once through the magnet (\(\theta_{f}\)).

Calculate the energy lost to friction using (156).

Now connect the resistor by plugging in both plugs into the wand.

Press the “Record” button on Capstone with the coil at rest between the magnet poles.

Rotate the wand to an initial angle of \(25°\) and let it go.

Press the “Stop” button after the wand has reached the other side.

Measure again the initial angle (\(\theta_{i}\)) and the angle to which the pendulum rises after it has passed once through the magnet (\(\theta_{f}\)).

Calculate the total energy lost using (156).

Highlight both peaks on the power vs. time graph and find the area under the curve. Use the “Area under highlighted region” tool in Capstone for this. Right-click the displayed value to set the numeric format. This area is the energy dissipated by the resistor.

Add the energy dissipated by the resistor and the energy lost to friction. Compare this to the total energy lost by the pendulum.

Compare these two values for the energy loss.

Post-Lab Submission — Interpretation of Results#

Make sure to submit your finalized data sheet with summarized data and cleaned-up plots (Excel sheet)

Paragraph of your results +/- uncertainties from your data. Make sure to include discussion of the following:

Do your experimental results for induced voltages from part 1 agree with the expected values?

Do your values for energy loss from change in gravitational potential energy ((156)) agree with the energy dissipated by the closed circuit (with resistor) agree plus friction of the rotary sensor?

What was the induced voltage of the coil of wire swinging into the magnetic field dependent on?

Looking at your plot from Capstone of Voltage vs. Time, there should be four spikes in voltage during one whole cycle forward and back; why are the first and second peaks opposite signs (positive vs. negative, look back on the wand’s circuit diagram and think about how current would flow), and how does that relate to Lenz’s Law?

Why is the voltage zero as the coil passes through the center of the magnet?

Why, for the Power dissipated vs. Time plot were there two peaks, but now of the same sign (i.e. both positive)?

Why, if you used a larger resistor, for example a \(10\,\Omega\) resistor in place of the \(4.7\,\Omega\) resistor, would the damping of the pendulum would be reduced.

Paragraph of your errors and estimated measurement uncertainties. Make sure to include discussion of the following:

Where might systematic (affecting accuracy) and/or random (affecting precision) errors be coming from?

What are your measured uncertainties, and, based on these uncertainties, how do your final results change? I.e. do your different measurement and slope uncertainties make your final results larger or smaller?

Change different variables by your best estimation of measurement uncertainties in your Excel sheet; what variables affect the accuracy of your final results the most?

If larger or small, are they more or less accurate to expected values?

How could you improve your random errors?

Were your systematic errors significant; how could this be improved if you were to re-run this experiment?

Reflect on this week’s lab; what did you learn?

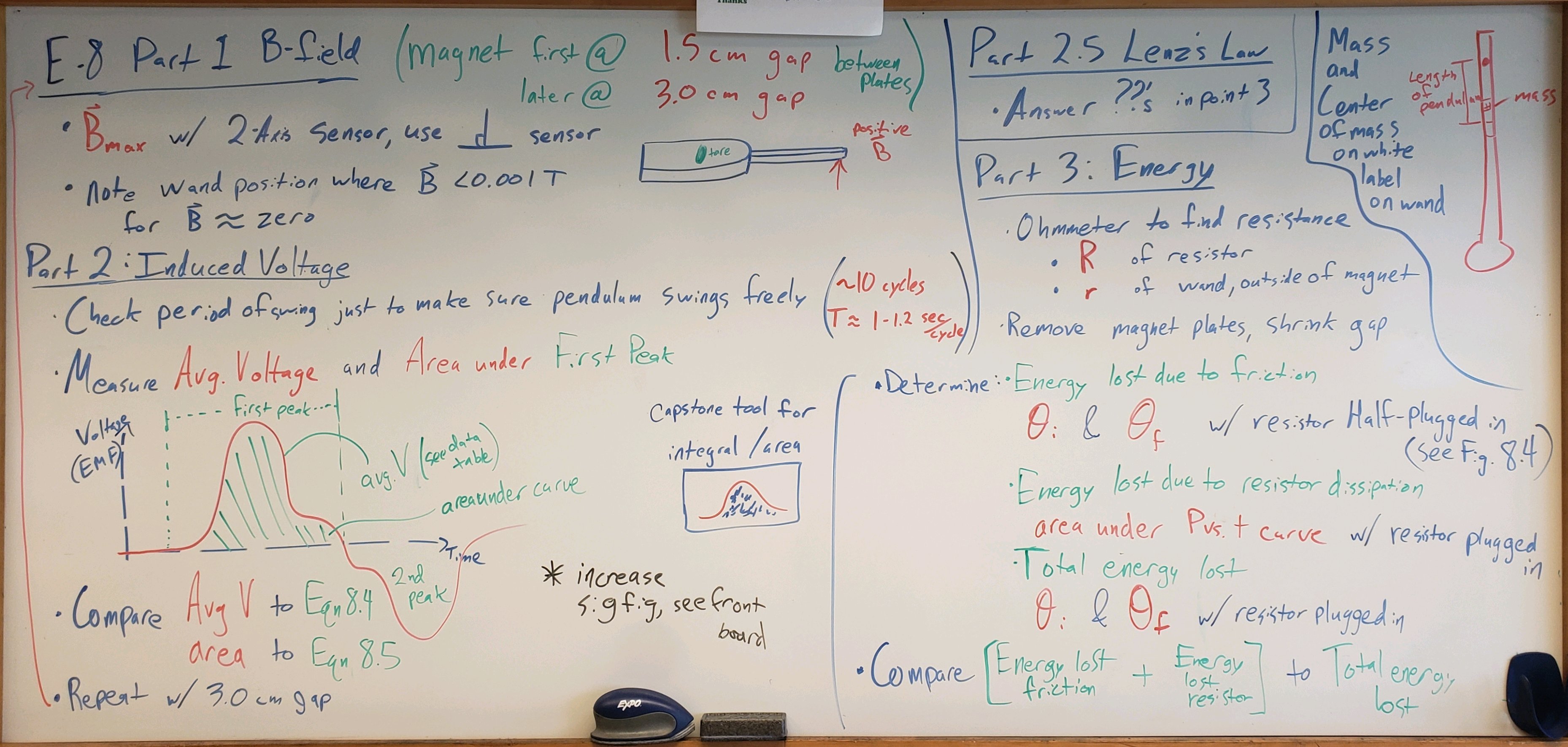

The Whiteboard#

Fig. 114 Overview.#

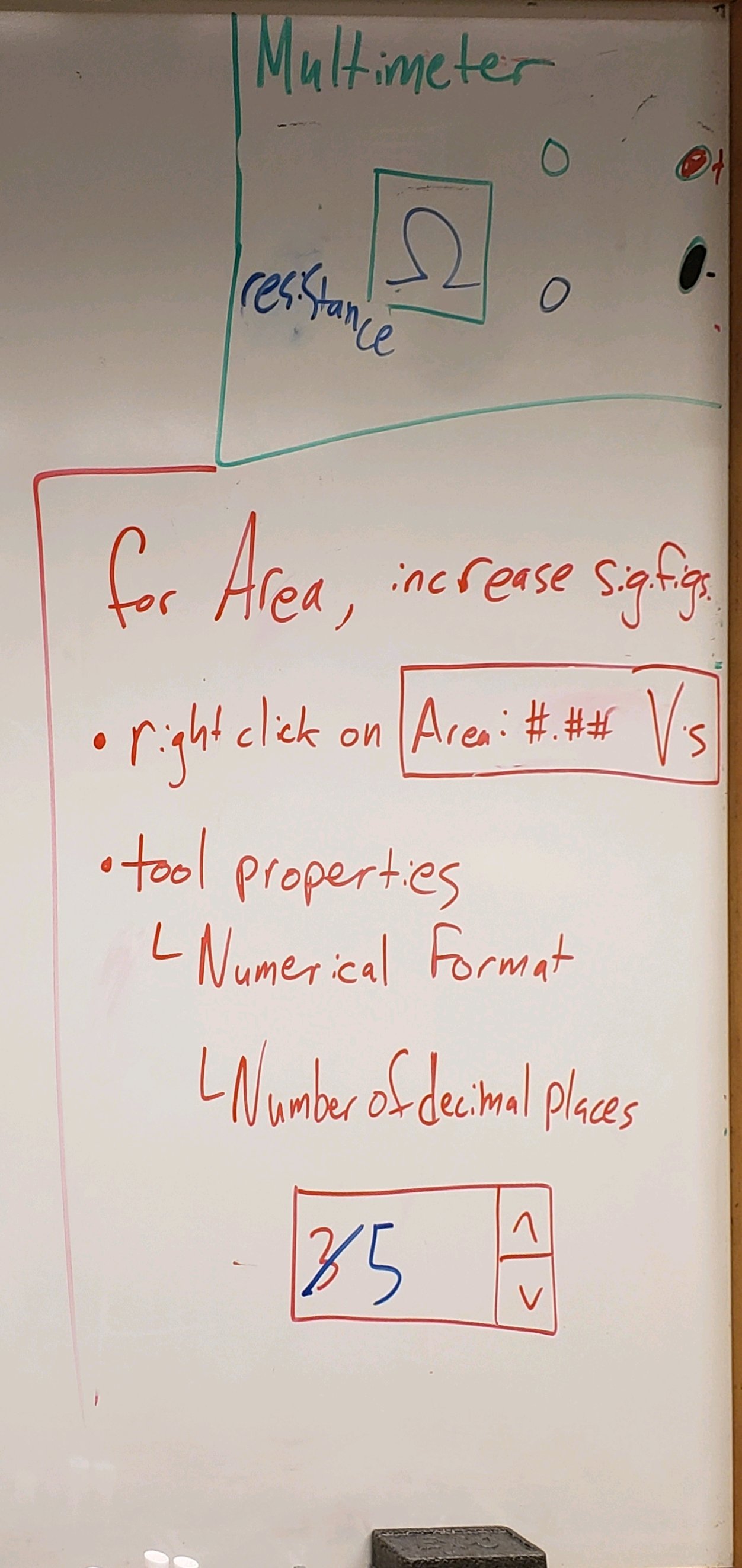

Fig. 115 Multimeter settings, changing significant figures in Capstone (must be done every new data run).#

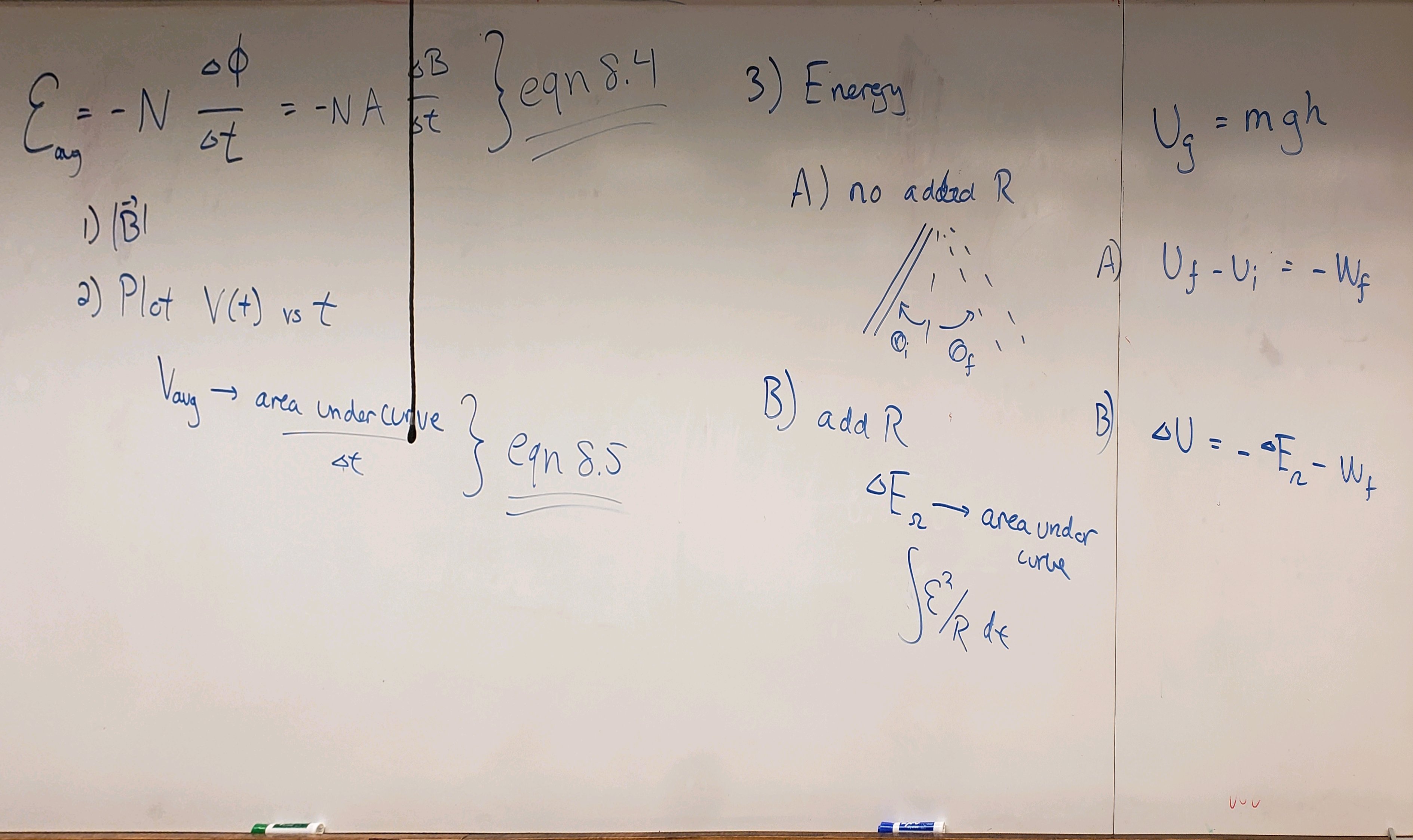

Fig. 116 Short notes on the three parts of the lab.#