Equipotential & Electric Field Mapping#

Background#

Overall goals and overview#

OVERALL GOALS

Use different electrode configurations:

Qualitatively explore the relationship between equipotentials (surfaces lines of constant voltage) and electric field lines.

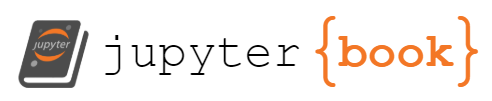

Electric fields are a convenient construct to analyze the electrical force between two charges. It is defined as the force per unit charge experienced by one charged body in the presence of one or more other charged bodies. The direction of the electric field \(\vec{E}\) is in the direction of the net electric force experienced by a positive charge. It is illustrative to represent the electric field distribution by lines that continuously point in the direction of the electric field (see solid lines in Fig. 78 right).

Fig. 78 Right) Equipotential (dashed) and E-field lines (solid) between two equal but opposite charges. Top-left) No work, no forces, along equipotential lines. Bottom-left) Electrical forces in direction of E-field lines.#

The amount of work required to move a unit charge between two points in an electric field is equal to the electrical potential energy difference between the points. The potential difference (voltage), \(V\), is defined as the electrical potential energy difference per unit charge between the two points (see Fig. 78 bottom-left). By convention, electric field lines begin on positive charge and terminate on negative charge (point from positive to negative).

If the potential difference between two points is zero, the two points are said to lie on an equipotential line or surface. Thus no energy is required to move along an equipotential surface. Since no work is required, there cannot be any electrical force tangential to the surface (see Fig. 78 top-left). In other words, there cannot be any electric field tangent to the equipotential surface, and so the direction of the electric field must be normal (perpendicular) to the equipotential surface at that point.

Finally, as there is always a unique net electrical force acting on a charge, there must be a unique direction to the electric field at that point. Thus, two electric field lines can never cross since the intersection would have two different, simultaneous field directions. Similarly, equipotential surfaces, which must be perpendicular to the electric field directions, cannot cross. Electrodes are conductors and therefore are themselves equipotential surfaces. Thus, the electric field lines at their surface must be perpendicular to the electrodes.

If equipotential lines are parallel to each other, so too must the electric field lines be parallel to each other. Similarly, if equipotential lines are curved, then the electric field lines will converge or diverge as they pass through the equipotential lines. It can be shown that the magnitude of the electric field increases as the electric field lines converge and decreases as the lines diverge. As equipotential surfaces get closer together, they must necessarily become more parallel to each other. Thus, the shape of the electrodes and the spacing between them dictate the pattern of the equipotential lines and electric field lines.

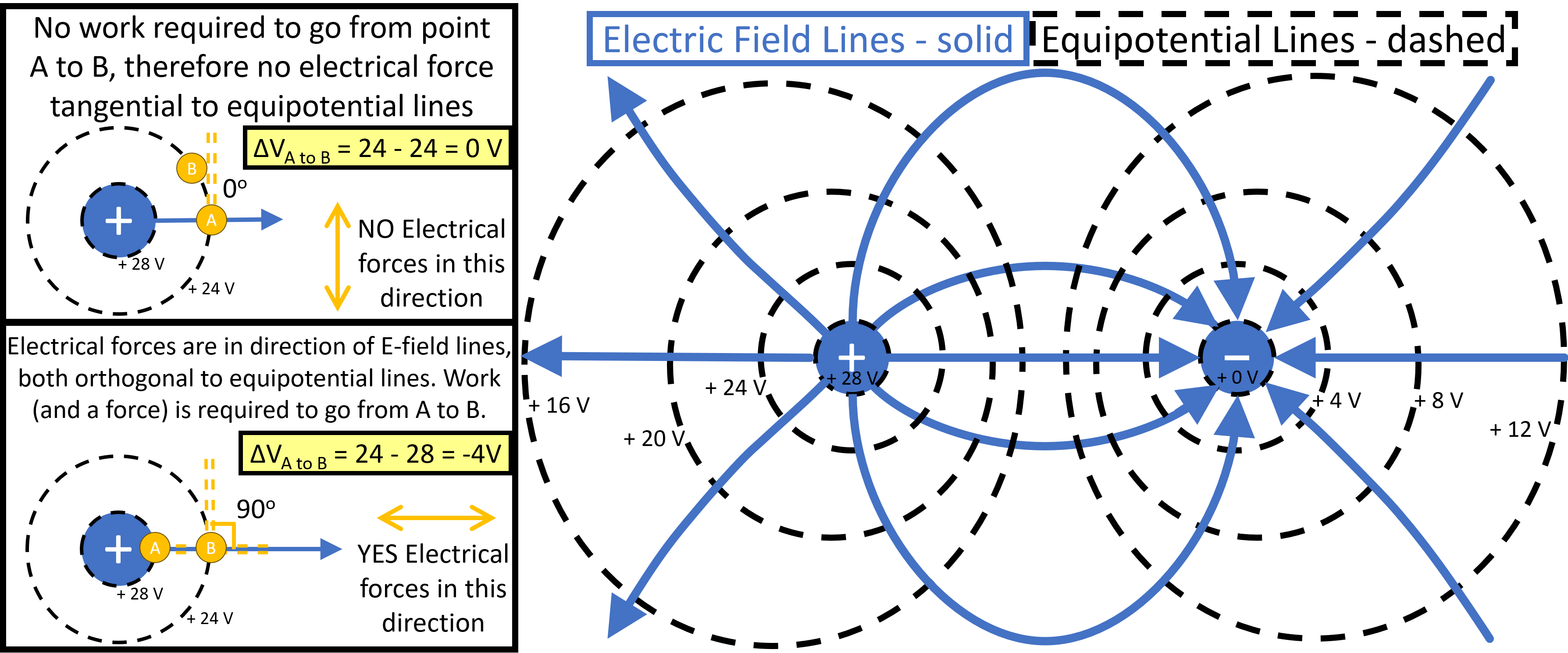

In this experiment, we will qualitatively establish electric field distribution between various pairs of electrodes on a sheet of conducting paper (shown wired up to power supply in Fig. 79 bottom left). With a voltmeter (setup shown in Fig. 79 top), we will measure the potential difference between points on the paper. By plotting lines whose points are at the same potential (i.e. zero potential difference between any two points, or points at the same voltage), we can map out a number of equipotential lines. Note that in three dimensional space, equipotentials are surfaces perpendicular to the electric field. On the two dimensional conducting sheets, equipotentials form lines perpendicular to the electric field. Since we know that electrical field lines must be perpendicular to the equipotential lines, we can sketch a representative family of electrical field lines using the conventions discussed above.

Fig. 79 Experimental setup. Top) general setup with all parts included. Bottom left) Example of wiring the electrodes and conductive paper to 24 V. Bottom right) Schematic.#

An example of an electrode configuration is illustrated in Fig. 79 bottom right. The dashed line indicates a possible equipotential line. In this example, it is specified by the positions on the paper whose potential with respect to the negative terminal of the power supply is 12 V. Moving the probe on the paper to other points where the voltage is 12 V generates the equipotential line. Since each point on the line is at the same potential, this is one of an infinite number of equipotential lines generated by this electrode configuration. The actual plotting (recording) of the equipotential lines and the sketching of the electric field lines is done on a separate graph paper whose coordinates match the conducting paper with its electrodes.

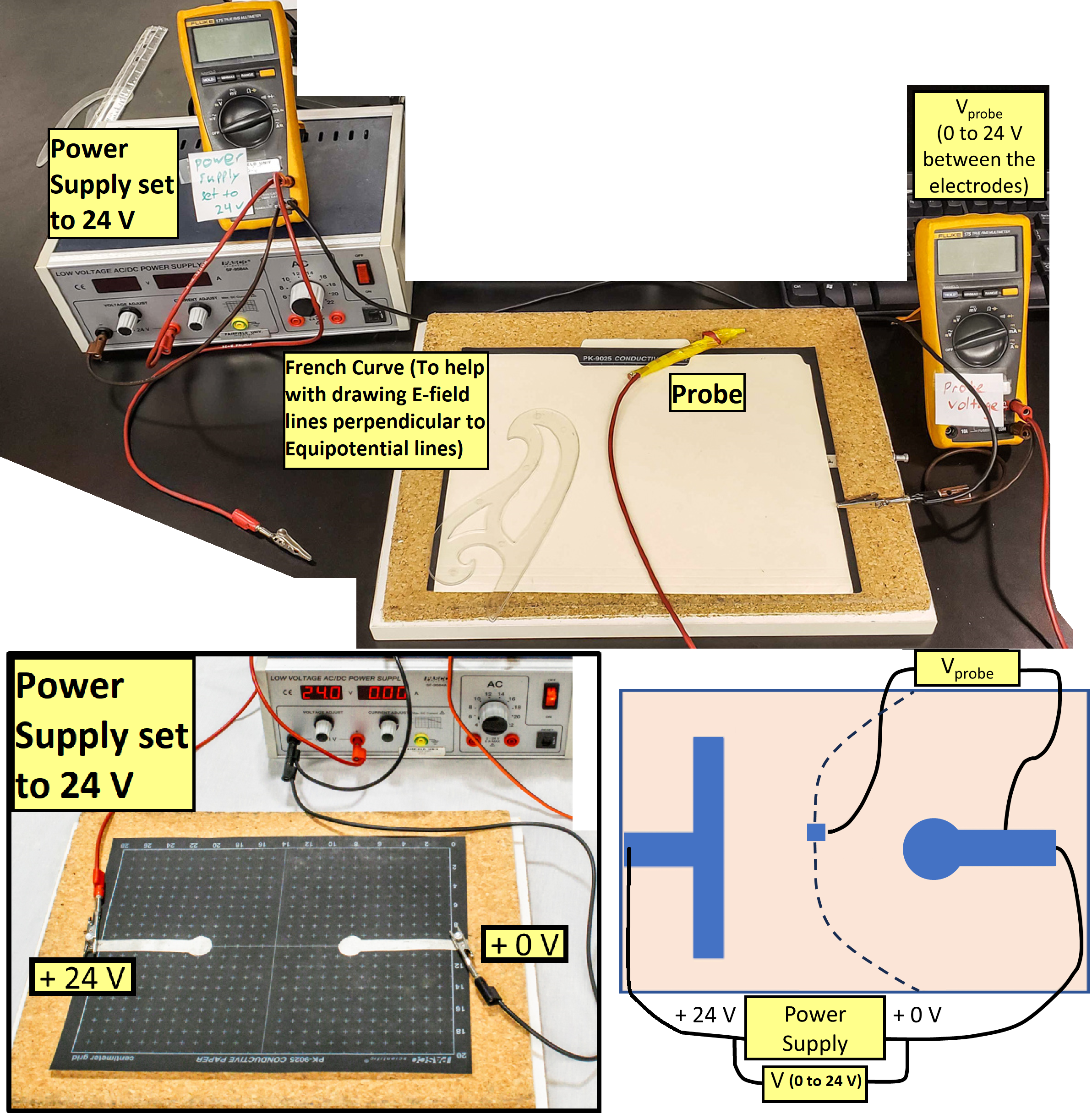

If we determine a number of equipotential lines for this electrode pattern we might get the pattern of ‘dashed’ equipotential lines shown in Fig. 80. Recall that the electrodes are also equipotential lines. Now we can sketch in a representative pattern of electric field lines; like the equipotential lines there are an infinite number of possible field lines. We know that the electric field lines begin on the positive electrode and end on the negative electrode, and they are normal (perpendicular) to all equipotential lines they cross without crossing other E-field lines. A few small arrowheads along the field line indicate the direction of the field. The field lines will be shown as solid lines to clearly distinguish them from the equipotential lines.

Fig. 80 Electric Field and Equipotential patterns drawn from edge to edge of the paper.#

Since the direction of the electric force on a test charge is always positive-to-negative by convention, the arrowhead direction of the field lines must be the same. For this example, we start with more or less evenly spaced starting points at the positive electrode. Consider a single field line leaving one of these points. It leaves normal (perpendicular) to the surface. As it approaches the first equipotential surface, the direction of the field line needs to be smoothly adjusted so it crosses it perpendicularly. Continuing to the next equipotential line, the direction of the electric field line is continually and smoothly adjusted to cross this equipotential perpendicularly. Continuing in this manner, the field line is sketched all the way to the negative electrode where it must end on the electrode perpendicular to the local surface. This drawing can be assisted by the use of a “French curve” whose use will be discussed later in the procedures.

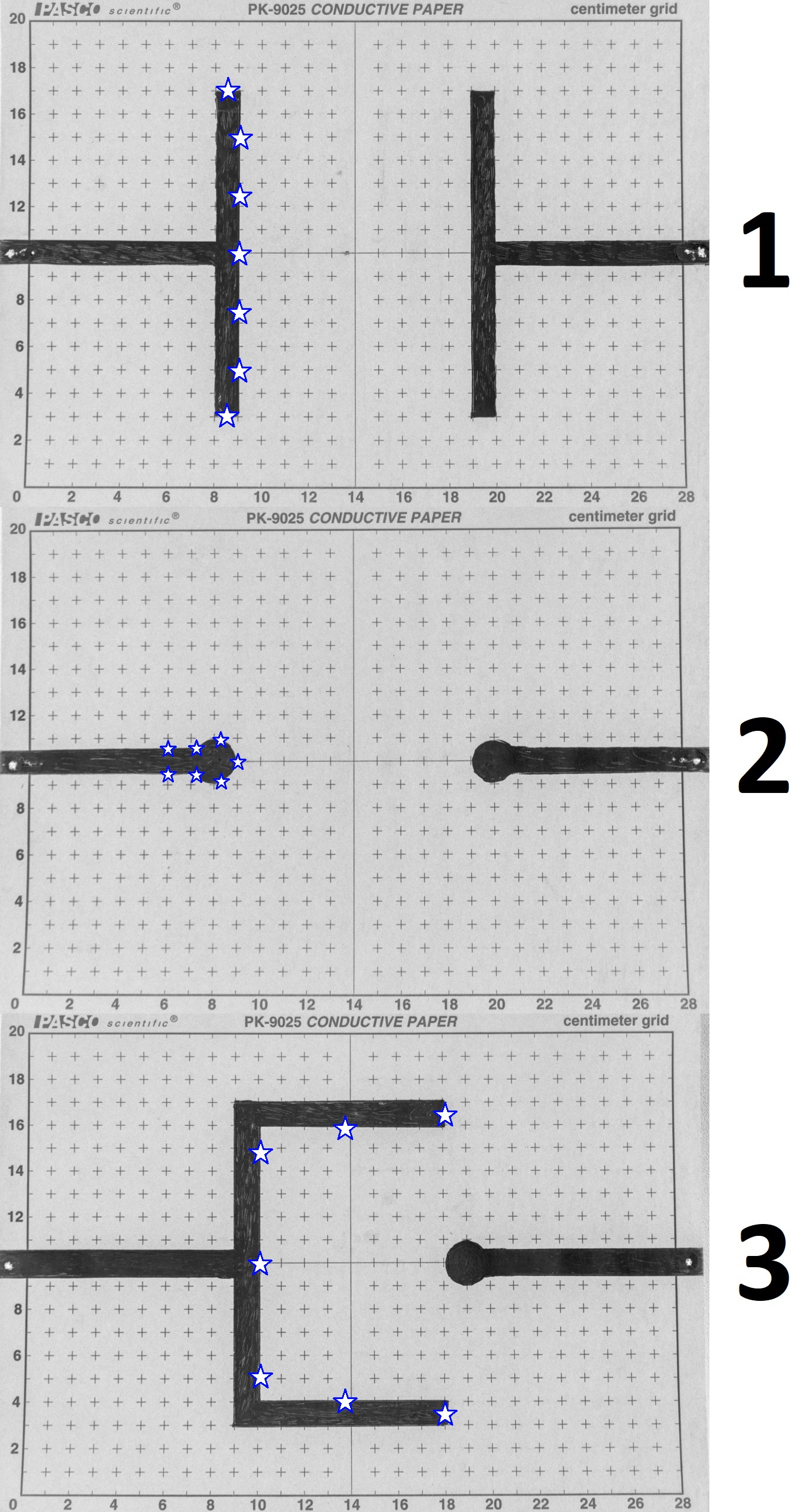

The electric field lines can be sketched most easily when there are a sufficient number of more or less equally spaced equipotential lines to guide the direction of the field lines. The number of electric field lines that are drawn should be sufficient to clearly show the characteristics of the pattern. The electric field lines should be evenly spaced along the surface of the positive electrode so the density of the field lines in the pattern will show the relative intensity of the electric field. In this pattern you can see the higher concentration of field lines as they approach the smaller radius surface of the right electrode. The same thing would occur at the sharp corners of the left electrode if we happened to start our sketching from a uniform spacing of field lines on the right electrode. The configurations you will characterize are in Fig. 81 which also show seven suggested positions on the left electrodes to initiate E-field lines (roughly equally spaced).

Equipment#

Depicted in Fig. 79 and Fig. 81.

Low voltage DC power supply, 0 – 24 V

Two Fluke multimeters – set to read DC voltage (one for power supply, one for probe)

Folder with three sheets of black conductive paper with different electrode configurations (see Fig. 81) and white photocopy of the same for plotting

Cork board with 2 metal push pins (for electrical connection to conductive paper)

x5 Banana plug wires connecting power supply to voltmeters and electrodes (via alligator clips) on conductive paper

x1 Banana plug wire in the red holder as the probe wire to determine patterns of equipotential lines

French curve for drawing curved E-field lines perpendicular to the equipotential lines determined with the probe

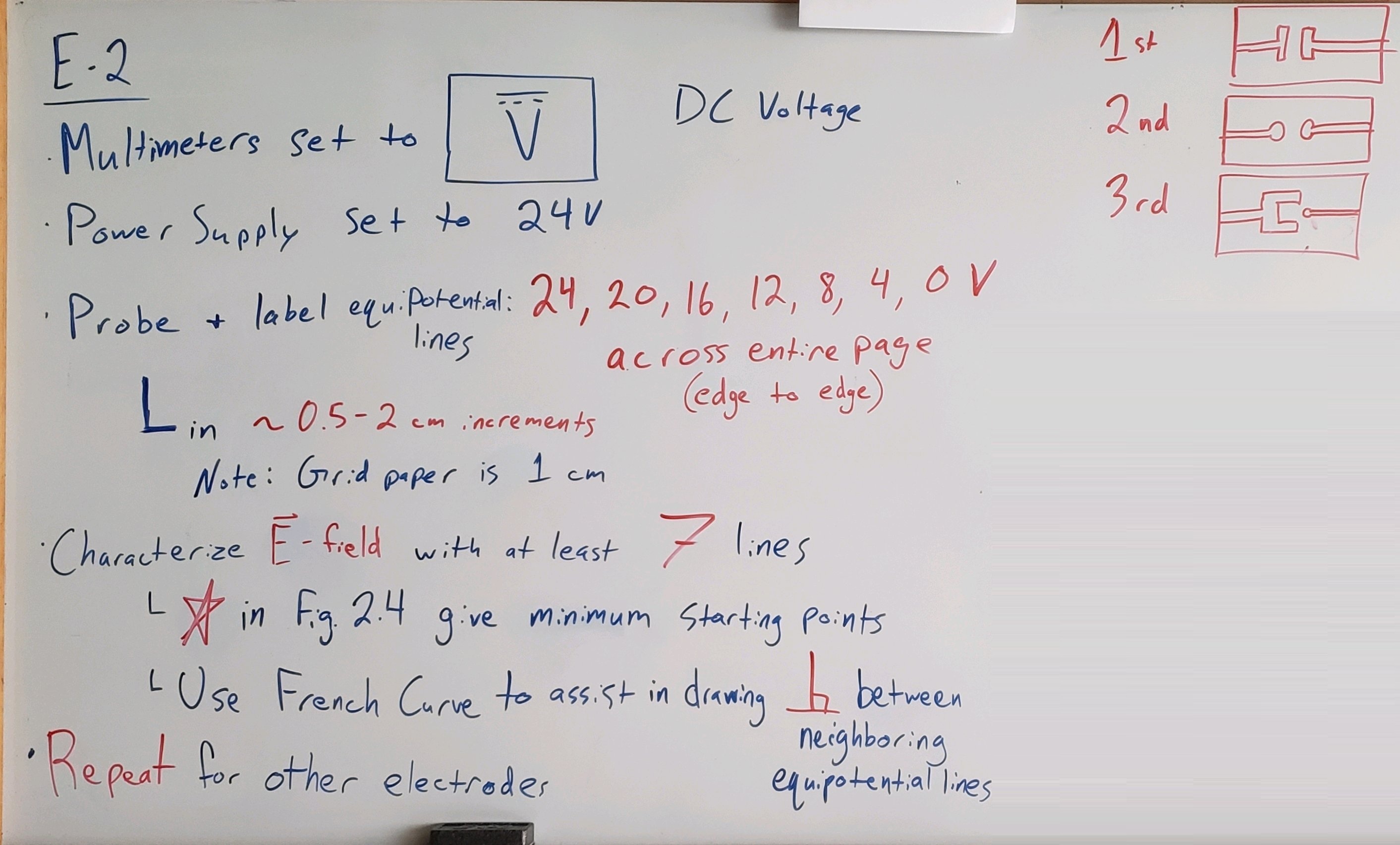

Experimental Procedure#

OVERVIEW

For three different electrode configurations:

Map onto paper equipotential lines:

Measure and record voltage at many locations from edge-to-edge across the conductive paper

Map electric field lines:

Use a french curve for orthogonal interpolation

Map at least 7 E-field lines, starting from the ⭐ starred ⭐ starting positions in Fig. 81.

Each person will complete at least one whole plot with: 1) dashed lines representing equipotential lines of 0 – 24 V in 4 V increments covering the page edge-to-edge – measured by testing voltage with the probe at 0.5 – 2 cm increments depending on equipotential curviness and 2) solid lines representing the E-field. There are three configurations (Fig. 81). Each plot should contain 7 measured equipotential lines/surfaces and at least 7 estimated E-field lines.

Fig. 81 Electrode configurations. The stars suggest starting positions for E-field lines.#

Each group will plot all three electrode configurations (see Fig. 81); each person will draw at least one configuration. Place one of these conducting electrode sheets on the cork mounting board and fasten down with a metal push pin at the end of the silver electrodes. Make sure the pins are pushed all the way down to make electrical contact with the electrode.

Refer to Fig. 79; connect both the positive terminal of the first voltmeter and one of the electrodes to the positive terminal of the power supply. Connect the other electrode similarly to the positive terminal of the power supply and first voltmeter. The probe will be connected to the positive terminal of the second voltmeter, while the negative terminal of the second voltmeter is connected to the negative electrode.

A photocopy of the electrodes on a sheet of graph paper will be provided for each of the electrode configurations. They will be used to record the points of the equipotential lines determined in the following steps.

Gently place the probe on the positive electrode and adjust the power supply so the voltmeter reads 24 V. Check that the probe is making electrical contact by moving it, with a very light downward pressure, from the positive electrode to the negative electrode. Verify that the voltage decreases smoothly from 24 V to 0 V. The whole sheet will be at 24 V or 0 V if a pin does not make contact; if so, reset the pins and check again.

With a very light downward pressure move the probe along one of the long sides of the conducting paper until the voltage on the first voltmeter is 20.0 V. Mark the point on the graph paper.

Now move the probe about a centimeter away to find the next nearest point as close to 20 V as possible and mark it on the graph paper. After having two positions marked, you can start to indicate the direction of the equipotential. The tangent to the equipotential will help you search for the next point. Move again and mark the next point and direction on the corresponding point on the graph paper copy. Continue in this manner until you reach the opposite side of the conductive paper. If it appears that the equipotential line is curving rapidly, as it might near a small radius edge of an electrode, it will be helpful to take more closely spaced points. These points must be connected by a carefully drawn, smooth curve, making sure they do not cross other equipotential lines, including the surface of the electrodes.

With the aide of a ‘French’ curve available in the laboratory, draw a DASHED CURVE through these points and tangent to the equipotential which can be defined as the 20 V equipotential line.

Now, move the probe along the edge and find a 16 V point and proceed to find and plot the series of points of the 16 V equipotential line from one side to the other of the conductive paper.

Proceed in this fashion in 4.0 V steps and plot the rest of the five equipotential lines between the electrodes and label all 7 equipotentials (24, 20, 16, 12, 8, 4, 0 V. Note: The electrode surfaces represent the zero and 24 V equipotential lines.

After the equipotential lines have been determined, draw in the corresponding electric field lines starting at one electrode and running to the other electrode. Use a ‘French’ curve and the technique described in the background section above. Sketch in at least seven SOLID lines to give a representative picture of what the electric field looks like (suggested, equally spaced starting positions are indicated in Fig. 81); add additional E-field lines as needed to ensure full characterization of the electric field including lines that may go off the page. Sketch lines including the areas at the edges. Recall that the electric field lines are perpendicular to the equipotential lines, including the electrode surface edges (Fig. 80). THESE SKETCHES MUST BE MADE BEFORE LEAVING THE LABORATORY. Compare them with similar figures in your text and if they are not satisfactory, then take additional data as necessary.

These field patterns should be carefully and neatly reproduced, on each graph paper with the corresponding electrode pattern. As with any graph or illustration, they must be clearly annotated with appropriate labels, potentials, polarities, and field directions. ALSO, INCLUDE THE PLOT-DRAWER’S NAME AND GROUPMATES’ NAMES ON EACH PLOT.

Repeat from Step 1 for each selected electrode configuration.

Post-Lab Submission — Interpretation of Results#

Note: For this lab, your results will be very qualitative.

Finalized Spreadsheets#

Make sure to submit all three of your finalized field mappings.

INCLUDE THE PLOT-DRAWER’S NAME AND GROUPMATES’ NAMES ON EACH PLOT.

Include all labels and markings as described throughout the procedure.

Post-lab Writeup#

In a paragraph, summarize your error analysis. Be qualitative, not only quantitative.

What are possible sources of systematic (i.e. affecting accuracy) and random (i.e. affecting precision) errors?

How could you increase your confidence (i.e. decrease you uncertainty) in your electric field lines (i.e. final results) considering your methodology from today’s lab? Consider electrode configuration 3 (Fig. 81 3).

In a paragraph, summarize the results you have determined in each case. Consider:

What was the point of today’s lab; what did we aim to discover?

How do the equipotential lines that you drew physically relate to the electrode spacing and shapes?

How do the E-field lines that you drew physically relate to both the electrode and the equipotential patterns? – What happens to your E-field lines when equipotentials were curved, or closer together/further apart?

If you placed an electron on an equipotential, say the 16 V equipotential, what direction would the electron move?

What do the electric field and electric potential patterns in electrode configuration 1 (Fig. 81 1) suggest about the electric field between the two plates in lab E-1?

The Whiteboard#

Fig. 82 Overview.#